Blog 167 - Marine Musings - "Kolams" and the Unheralded Sunrise Artists

- ranganathanblog

- Oct 12, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Oct 23, 2025

Of Sunrises and Sunsets

I had a habit that I preferred never to break when I was a Chief Engineer at sea. I would be up-and-about by 5 every morning and, by 5.30 - or earlier - i would be on the Bridge when the vessel was at sea, having my first cup of the day of coffee, brewed by the Chief Officer who would, then, be on watch.

Navigational watches are lonely. Except for the Helmsman, who would be acting as a Lookout, the Chief Officer - or any Duty Officer for that matter - would be all alone in an endless stretch of the universe, as ships - showing only their navigational lights - passed each other silently, with only the sound of the wind or the small whisper of the waves upon the hull. Most times, the sea would be empty of any presence barring your own.

Into that atmosphere of quiet I would intrude into the reverie of the Chief Officer, seeking a cup of coffee. Almost all Chief Officers would welcome my arrival to such an extent as to ensure the coffee would be almost ready when I reached the Bridge. Post retirement, I can truthfully say that those cups of coffee were the ones I have enjoyed most in my life.

For me, the ritual of the cup of coffee hid a very deep metaphysical meaning. The sun would rise during my presence on the Bridge. A few steps taken would land me on the Bridge Wing which gave me the advantage of seeing the sun rise, whatever be the heading of the ship.

Of the thousands of such sunrises, I do not recall even one similar in scope, beauty, aura to any other for comparison.

The sense of tranquility that surrounds such a sight is, each, a private moment between the Maker and self. The peace that pervades the mind extends into personality and resurfaces as patience, introspection before action and a more humane view of the world.

Somehow, sunsets did not move me as much, except in the scope of their beauty. Sunsets were more spectacular than sunrises, covering a larger quadrant of the sky with their brilliance.

The Canvas shifts to the Earth

I, for one, was rather surprised by my eclectic taste when I veered away from writing about ships to take up an off-the-beaten-track topic like Kolams. "கோலம்" in Tamil.

But I can truthfully say that, since childhood, Kolams have fascinated me. 7 decades later, I am giving form to a subject that has enthralled me.

This article is part of a blog of mine. One of the good things about blogs is that one can write about what is dear to your heart, even if nobody reads them, as long as one does not hurt others.

Historically, ‘Kolams’ can trace their ancestry back several thousand years, from the time temples were constructed, the ‘Kolams’ coming into vogue in celebration of the Deity. From there to households was just a meagre step.

The sky is the Canvas upon which the Ultimate chooses to sketch his “Kolams”. I use the word ‘Kolam’ specifically in a South Indian context, because what He deigns to portray on his Canvas every day, is portrayed in a different form across millions of households on a daily basis by the unsung, unheralded women artists who articulate their works of art every morning, only to see it disappear on an hourly basis till nothing is visible - trampled, run over, rained over.

‘Kolams’, by themselves, are the heralds of the day. The warmth of the sun. The brightness of a beautiful day. The promise of better times.

I speak here of the millions of morning artists who adorn their home fronts with sometimes lavish, sometimes conservative, sometimes simple and plain, designs that are simplistically called ‘Kolam’.

To define a ‘Kolam’ is to try and package an art form into a simple sentence. The best I can do is to try and explain the ritual behind the rendition of ‘Kolams’ that transcends spirituality.

The ritual starts much before sunrise.

The lady of the house - or one of the daughters- sweeps a major portion of the road fronting the house, using a broom made from the central core sticks of the coconut tree branches, (‘Thenna Thodappam), after removal of the fronds. In today’s world, where the word ‘ecology’ is bandied about with abandon, this humble broom symbolises the wisdom of our ancestors, who made use of every part of the coconut tree, wasting nothing.

Then would come the sprinkling of water on to the road. Decades ago, this water would contain a mix of cow dung. Using cow dung and water, the mud roads in front of the house would cake up and harden, preventing dust from entering the house.

The verandah of the house, being made of red cement or tiles of mosaic or marble or granite, would then fall prey to the attention of the lady. It would be swept and washed.

In the decades of yore, the ladies would then retire for a bath and, in the case of auspicious days, a ritual bath where turmeric plays a part.

The Ritual of the ‘Kolam’ : Analysing the Connotations of a Kolam

Then would come the ritualistic rendering of the Kolam.

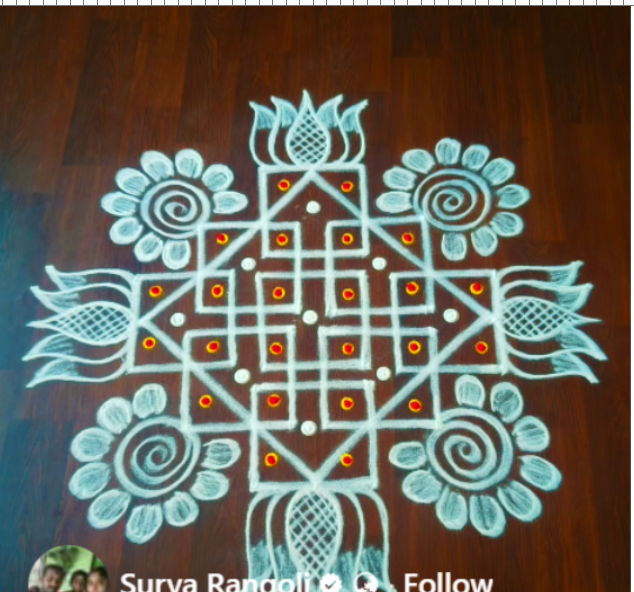

While these artistic designs are pan Indian, the Kolams of the south differ from the designs of the northern states in the use of the powders for the Kolams. In the Northern states, it is called ‘Rangoli’, as a lot of coloured powders are used. The rangolis are more random in shape, design and size, whereas the Kolams are on the basis of mathematical measures.

Indeed, some of the very elaborate Kolams are based on dots rendered on the ground as per Fibonacci Numbers. 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34 etc.

The simplicity or the elaborateness of the Kolam depended entirely on the importance of the day.

Either the Almanac or the notations of the daily tear-away calendar would have been consulted the day before, to plan for the Kolam.

Whatever be the design of the Kolam in front of the house, it symbolises several realities.

It says

We are part of the social fabric of this area.

We live here.

We are happy here.

We welcome you.

To the non human wanderers and inhabitants of the world the ‘Kolams’ say:

To the ants, the Kolam says “Come and partake of the finely powdered rice particles - they are for you and your family, to transport to your home and store in your granaries for a rainy day”.

To the chameleons and lizards that inhabit the crevices of the road, the Kolam says “Come and eat your fill”.

To the birds that inhabit the skies, the Kolam says “Come and peck at the rice flour without fear. It is our daily offering to you. Come, break your fast”.

The Kolam rice flour is just finely ground raw rice - as opposed to boiled rice - that easily flows between finger tips.

The dexterity of the fingers is what matters in achieving the thinness or the thickness of the dots to be placed or the lines to be drawn.

It is totally freehand, without recourse to any measuring instruments that relies solely on the lady artist’s sharpness of eye and the nimbleness of the thumb, forefinger and - when needed for thicker lines - the middle finger.

When at home and in my morning runs - when young - and walks - at a more sedate age - before sunrise, I came across thousands of such morning artists who would be either squatting or kneeling or bent over the specific area of the ‘Kolam’.

Being a person for whom drawing, as a subject, was anathema - even today I am perplexed at how I passed my Engineering Drawing exams - I would marvel at the ease with which they would proportion the whole Kolam, the sureness of each stroke, whether straight or curved, the left hand side of a curve as defined as the right hand curve.

What did the Kolams say to a passerby

The absence of the Kolam is as revealing as the presence of one.

The absence of the ‘Kolam’ in front of the house may signify illness of the lady of the house or bereavement in the family. It could also be the family performing a ‘shraadhh’ on the death anniversary of the parents of the head of the family.

The presence of a simple Kolam signified an ordinary day.

The presence of a more elaborate Kolam meant that the family was celebrating an important event.

If the elaborate Kolam was traced at the borders by a red paste - made from red mud, called ‘Semmann’ ( செம்மண் ) - it signified some event of a religious nature is to take place in the family.

If this is accompanied by the presence of entwined mango leaves strung up at the entrance door of the house, it means a family-only religious ceremony in-doors. Example - the naming ceremony of a new born or a religious ‘homam’ is being performed or even a wedding anniversary. Or a precursor to a wedding in the family - the ‘nischyadhartam’.

If the elaborate ‘Kolam’ is further accompanied by the presence of two banana plants tied to the gate posts, it means invited guests are also attending. The presence of the banana plants is also a GPS tracker for guests who do not know the exact location of the house. Example - the first birthday pooja of a new born or the 60th or 80th birthday of the patriarch of the house, when the family does not want an elaborate public ceremony.

All Hindu festivals like Vinayak Chathurthi, Durga or Lakshmi or Saraswati Puja, Navarathri, Deepavali, Pongal, all New years - the average reader may be surprised at the number of New Years that are celebrated all around India - bring out the artistic talents of the ladies, with neighbours admiring each other’s designs.

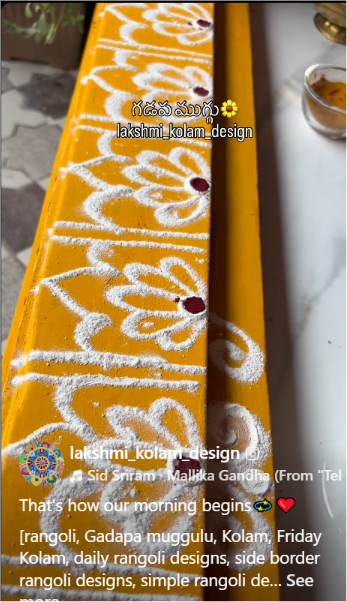

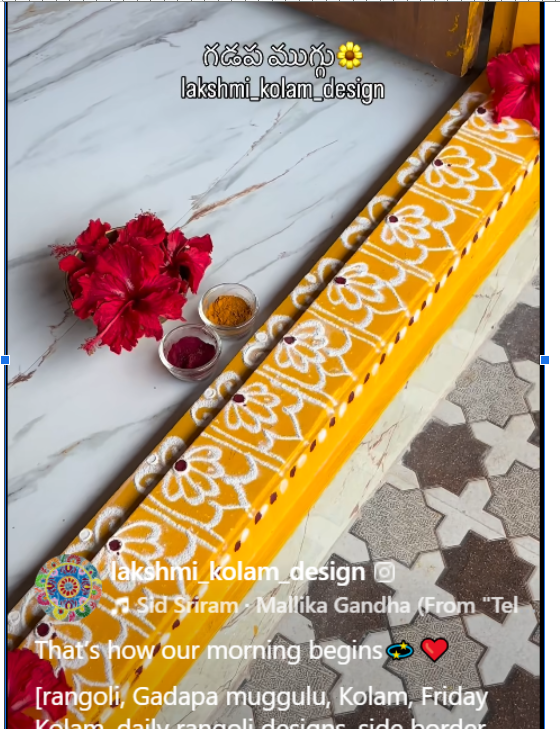

The Significance of the Households’ Doorstep

One of the areas of the household that plays an important part in the design of Kolams is the main doorstep - the wooden or cemented beam of the main door which is underfoot.

In Hindu homes, the wooden doorstep, known as the vaasapadi (வாசப்படி) is a sacred boundary that separates the purity of the inner home from the potential chaos and negativity of the outside world. Its significance stems from both Vastu Shastra, the ancient Indian science of architecture, and deep-rooted spiritual beliefs.

The doorstep is revered as a gateway for positive energy and a barrier against negative forces.

Welcomes prosperity: The doorstep is considered the threshold where the goddess of wealth and prosperity, Lakshmi, enters the house. It is often cleaned and decorated with designs like rangoli to invite her blessings.

Filters energy: By physically raising the floor level several inches at the entrance, the doorstep acts as a symbolic filter, preventing negative energies, evil spirits, and misfortune from crossing into the home.

Significance of the Swastika in South Indian Kolams:

The ‘Swastika’ is one of the oldest religious, cultural and civilizational symbols, respected and revered for millennia only to be maligned and tarnished in the 20th century through its use by the Nazis, albeit in a slightly different form.

The German Nazi Swastika

In South India, the swastika is a significant religious symbol used for good fortune, well-being, and prosperity in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. It is commonly seen during Hindu ceremonies like weddings, festivals such as Deepavali, and in homes and businesses to invite positive energy and luck. The symbol's use in India predates the Nazis' adoption and has an entirely different meaning, with the Indian swastika having a flat, horizontal base while the Nazi version is tilted at a 45-degree angle.

How the Kolams are depicted

Let us go on a small journey depicting Kolams at various stages of elaborateness. Let me, here, pay homage to Facebook for most of my images that I intend to show piece here.

‘Kola Maavu’ is the rice powder ingredient used on a daily basis bought from the old lady who sings her wares of ‘Kola Maaaaavu’, ‘Kola Maaaaavu’ in the early hours of the morning. In an astonishing mix of professions, the younger and slightly more educated of them, double as house agents and have specific information of houses on rent in the area.

While the rice powder is the main ingredient used on a daily basis, there is another variant used on festive occasions. It consists of a slightly watery paste of the same rice flour, called ‘maa kolam’ or ‘maavu kolam’. Instead of leaving rice grains behind, the paste forms a mild paint of white on the surface.

Maavu kolam is a traditional Indian rangoli or floor drawing made with a wet rice flour paste instead of dry rice flour. Also called ‘arisi maavu kolam’ or ‘maa kolam’, it is often drawn with thicker, wavier lines, and is commonly used during festivals and auspicious occasions because the wet paste can last longer.

Some of the images are shown as a progression, to showcase the intricacies involved.

The next stage - Part 3

The perfect symmetry

One of the more artistic designs. No compass for getting the circle and radius right - only placement of dots. The traditional dry rice powder is used. The surface is one hardened by repeated use - over months - of water + cow dung. One of the unwritten rules of this type of ‘kolam’ is that every line connects to another, however complicated the loop design. In engineering parlance, this is known as a ‘closed loop system’.

Many such street-wise or area-wise or town-wise competitions take place during festive periods, the prize money running into lakhs from sponsors.

The Decoration of the Door Step - Vaasa Padi - வாசப்படி- The Threshold

As explained before, the Vaasa Padi plays a very important role in a Hindu home. By custom, one is not supposed to put your foot on it when entering or leaving. Cross it without planting your foot on it.

For any function, the doorstep is decorated elaborately. After cleaning with a wet rag, a watery paste of turmeric powder - haldi - மஞ்சள் is applied on to the step as well as the side posts. Vermilion - kumkum - குங்குமம் - is one of the ingredients used sparingly, just to bring a brighter colour to the design, just as turmeric powder.

Preparing and decorating a ‘Vaasa Padi’ - step by step

Part 3

Another beauty

Part 3

Part 4

The Finished canvas - Part 5

And, finally, a Terrestrial Artist's 'Kolams' who used the fields of an English Farmer for his canvas

Comments