Blog 166 - Marine Musings - Lifeboats and Accidents - Have they become synonymous?

- ranganathanblog

- Sep 30, 2025

- 12 min read

LIFEBOATS AND SAFETY AT SEA

Lifeboats, by supposed definition from the bodies - such as SOLAS - that define such things, are the last resorts of safety and life preservation in the event of a vessel going under.

(By the way, “the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) does not provide a singular, simple definition of a lifeboat but sets detailed technical requirements for their construction, capacity, stability, and equipment to ensure safety during an emergency. Key aspects include being properly constructed with sufficient stability and freeboard, having a rigid hull and a certificate of approval, being strong enough for safe launching, and being equipped with the necessary survival equipment)”.

Which means that they can be safely lowered and boarded, then launched and made to distance themselves from a sinking ship. The rules that regulate lifeboats are as simple as that.

The simplest of philosophies that one can attribute to lifeboats are

Retention on board, in a safe manner, for the ultimate safety of crew, passengers.

Lowering from the ship in a safe manner.

Boarding of all survivors in a safe manner.

Getting the lifeboat away from the sinking ship in a safe manner.

Surviving the next few days or, if need be, weeks till rescued, in a safe manner.

The commonality of all the above is the use of the phrase ‘in a safe manner’. Which phrase should be the dominant tone of any regulating body that envisions the process and mandates laws for the

construction of the lifeboat, its interior and its provisioning

Its placement on board and securing and launching arrangements

Its lowering mechanisms and necessary machinery for doing so

Its provision of needed survival equipment when boarded

Over millenia, the populace have braved the seas. At first, it was in small boats that never sailed beyond the sight of their villages, mainly for fishing. Then came that spark, that spirit of adventure, that every seafarer retains even today, that caused him to sail beyond the horizon, only to discover that the horizon extends forever. His first foray into exploration took him along the same coast that he resided in, only to discover many settlements such as his - that, later, became the basis of a united tribe. The further he went along the coast, the more diverse were the people, the language, the customs, the might.

The further he went beyond the horizon, he found he needed more hands - to row, to handle the sails, to steer, to navigate. More hands meant bigger boats. Trade commenced, with the advent of space for cargo. Boats became ships. For cargo and crew to be moved from the boat to the shore and vice versa, smaller boats had to be carried on board.

Initially, these smaller boats were not called lifeboats. Depending on the usage, they had several names, the construction of each being different from the other.

Tender: A general term for a boat that serves a larger vessel by carrying passengers, mail, or supplies to and from shore.

Dinghy: A small, often open boat that can be used as a tender or for recreation.

Pinnace: A light boat, often rowed but capable of being sailed, used to ferry passengers, mail, and provisions during the Age of Sail.

Whale Boat: Probably the most romanticised of the family of boats, where the boat is lowered in any type of sea, on the cry of ‘Daar she blows”. It was the rawest form of seamanship then known to man and continues to be so. Man against the elements. Man against the largest creature then known to man. A boat rowed towards the whale. A hand thrown harpoon to pierce through the whale’s skin. The whale threshes, dives and speeds away, pulling the boat along, as the harpoon is tethered to a rope. Hours of fighting the whale, then towing it back to the ship, to be lifted on board. Contrast this with today’s whaling ships that have missile launched harpoons with detonators, aimed from the whaling ship directly.

These were all boats without engines. Oars and sails were the sole propellants. Your attention is drawn to my last blog INSV Tarini, where two courageous Indian Navy female sailors circumnavigated the world on a sail driven 56 foot sloop.

The first Lifeboats were shore based and had their genesis in boats that were launched by rescue crew near lighthouses, to rescue ships that were wrecked off the coast of England.

The SS Adventure was the first ship to be equipped with what would become known as the first lifeboat, a purpose-built vessel designed by Henry Greathead in 1789. After the SS Adventure ran aground and its crew drowned in a storm, a committee in South Shields, England, commissioned the design and construction of a new lifeboat to prevent future tragedies

Before the Titanic tragedy, the number of lifeboats that the vessel was mandated to carry was determined by the vessel’s gross tonnage, which meant that the Titanic needed to carry only 16 lifeboatss as per the law, whereas she was designed to carry 64. The loss of the Titanic brought into focus that the number of lifeboats should be crew + passenger centric and not gross tonnage centric.

The sinking of the Titanic and the uproar that followed gave rise to the first SOLAS convention. (SOLAS - Safety of Life at Sea).

SOLAS History

There were only 13 countries which adopted the very first version of SOLAS held in London in 1914. This was the maritime community’s response after the sinking of RMS Titanic which claimed more than 1,500 lives in 1912.

However, the treaty did not come into force due to the occurrence of World War 1.

Since then, there has been four other SOLAS Conventions:

The second, which entered into force in 1933.

Third, which entered into force in 1952.

Fourth, which entered into force in 1965, and

The fifth, adopted in 1974 which entered into force in May 25, 1980.

The 1974 Convention is the version currently in force and is unlikely to be replaced by a new one. Over time, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) introduced amendments through the Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) due to accidents and technological advancements.

A Pictorial Representation of the History of Lifeboats Through the Ages

The crane needs POWER from a reliable source to operate the lifeboat.

LIFEBOATS - Tracing the voyage across centuries

First came the open lifeboats, with oars and sails included.

My first ship - in 1970 - included one lifeboat with oars and the second with Fleming Gear. The Lifeboat gear included canvas sheets and stanchions that could be raised to cover the boat, as a measure of keeping the elements away from the survivors in the boat.

Lifeboats with engines was the next step.

Then came the enclosed lifeboats that shielded all from the elements, mootorised.

Till this stage, the improvements in Lifeboat design were humancentric, based on the safety of the humans who would board the Lifeboat.

Till this stage, the actions and procedures in abandoning ship using the Lifeboat was simple.

Removing Harbour Pins and Gripes

Using ropes, blocks and tackles, bowsing tackles and tricing pennants, the boat was brought to the embarkation deck. Crew / passengers boarded.

Using ropes, blocks and tackles, the boat was lowered to the water.

Rate of descent was controlled by those using the block and tackle.

Unhooking the boat was a simple matter. Release the hook.

It then was rowed away to safety.

If it was a trial run, get the Lifeboat back into position and hook back the boat.

Then came the steel wired falls, which could not be controlled by hand. They required a braking mechanism for a controlled descent. A Drum was added for the falls, a centrifugal brake introduced to control the speed and a weighted lever was incorporated to disengage the brake when necessary for the lowering process.

An engine and shafting was fitted in the boat to run a propeller.

The boat was raised by a handle to rotate the wire drum or a motor attached to the wire drum.

Even till this development, there were no inherent dangers. The only problems stemmed from corrosion of davit wires - ‘falls’ - and centrifugal brake problems, where the brake pads or springs required renewal or the brake drum wore down or was scuffed.

The Lifeboat, per se, used to be lowered and lifted without any problem, as the hooks were easily removable and attachable and had no specific ‘setting’.

The first signs of trouble with lifeboats came with the introduction of the ‘on load release’ and ‘off load release’ mechanisms that were incorporated.

It is a common practice, during trials, to have the Chief Mate, Bosun and a couple of ABs to prepare the boat for lowering and unhook the boat when in the water.

The hook rigging and locking - before the Lifeboat is lifted out of the water - is also done by the same staff, under the supervision of the Chief Mate or Second Mate.

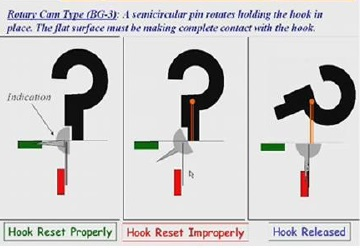

Just as a crash course in the operation of the mechanism for ‘on load release’ and ‘off load release’, I have downloaded the following 20 images from various sources, just to let all know how complicated is the procedure which exists even today on many ships.

ONE

TWO

THREE

Hand Drawings - thanks to Nihal Gupta (You Tube)

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

When there is a Lifeboat accident, the cause is always ‘human error’, not a ‘manufacturer’s 'defect’ or ‘poor design’.

Some of the components in today’s Lifeboat systems

Some aspects of Accident Reports

An MAIB (Marine Accident Investigation Branch) Study found that a root cause of many of the accidents was the over-complicated design of the lifeboat launch system and its component parts, which in turn required extensive training to operate. It also found that personnel incurred many risks. It identified that training, repair and maintenance procedures fell short of what was necessary, and that there were extensive problems with manufacture, construction, maintenance and operation.

Operating cables: The cables are usually of a type where an inner multi-strand wire slides within an outer sheath; sometimes referred to as bowden or morse cables. They offer a lightweight, cost effective and simply installed method of transmitting the usually moderate forces and motions required to operate most hook designs. The MAIB has found, however, that these cables can seize if the stranded wire becomes corroded. This can result in the on-load release hook failing to close properly when being reset. This in turn has resulted in inadvertent release later. Once corroded these cables cannot be repaired effectively, and have to be replaced. The evidence shows that management and crews are often unaware that such replacement is necessary. In response to one MAIB recommendation, a manufacturer amended its on-load release hook operation and maintenance manual to emphasise the importance of replacing damaged or corroded cables. It is not always the case. It is known that some other manufacturers do not draw attention to the inherent dangers of not replacing corroded cable.

Complexity of design

Investigations of several incidents have found that on-load release hook systems are complex and difficult to understand without having an in-depth knowledge of their mechanism and the operating instructions.

One hook design associated with a particularly serious accident relied on very fine engineering tolerances being maintained. Wear, combined with fretting and corrosion, affected the forces on its components and its ability to resist spontaneous opening. Its designers and type approval organisations paid insufficient attention to the hostile environment in which it had to function, such as salt air, weather and vibration. There was also a failure to recognise how seriously these conditions would degrade the hook’s performance. The MAIB is uncertain whether the existing testing requirements for this particular system are sufficient to address these very real concerns. It believes that a unified testing document would help. Automatic approval should not always follow when a system performs the tests presently required by SOLAS. Consideration must also be given to the likely ability of the system to perform in the marine environment between surveys and inspections. Crews rarely possess the necessary engineering knowledge to fully understand the system operating principles. In several accidents the complexity of the design has been clearly linked to maintenance and operating problems. This complexity has not always been appreciated, nor the need for maintenance by staff with specialist knowledge recognised. Without specific training for the equipment in use or easily understood and high quality instruction and operation material, seafarers are unlikely to acquire an adequate understanding of these designs. This has been shown to have an adverse influence on the quality of on-board maintenance, and has also led to sloppy and dangerous operating procedures. The need for reliable and comprehensive maintenance is paramount; there is sufficient evidence to show this is not being achieved in a number of vessels. The MAIB believes that the need for such quality maintenance based on an in-depth understanding of the design and mechanisms is so important that only the manufacturers and their agents should service such systems, or personnel who have undertaken a manufacturer’s approved course. This is supported in the text of the 1996 Amendments revision to SOLAS, which requires thorough examination and test during surveys by properly trained personnel familiar with the system.

Some Failures and Accidents

What would I want in a Lifeboat, as a seafarer and one who is assigned not only operate the boat but also maintain it?

Simplicity of hook design, so that all on board can operate it. It is to be noted that those trained operation of the hook may not be available at the time of abandoning ship.

Moreover, it is at the resetting of the hooks at the time of retrieval of the boat during trials that every (next) launching operation depends. The simpler the process, the more the guarantee of its success.

With today’s totally enclosed boats, there are not many defects that one can point out in the interior of the boat. Moreover, with efficient transponders, navigational satellites, the chances are that a Lifeboat will be located within the hour, with rescue being only a few hours away.

Except for the fact that one would have to climb down an embarkation ladder to reach it, the LifeRaft is about the safest piece of rescue equipment on board all ships. No hooks, no chance of falls parting or hook opening out in the middle of the launch. Simple expedient of detaching the attaching straps and allowing the raft to tumble into the water and watch it unfold. More or less from any steep angle of list. And, if a seafarer cannot negotiate ad climb down an Embarkation Ladder or a Jacob’s Ladder, he should not be on board.

Recent experimentation with - and installation of - Automatic Inflatable Marine Evacuation Systems

Although I have not personally come across this during my sailing days, it seems

Easy to install

Easy to operate

Can be deployed even whn the ship’s list is high

No maintenance on board, only inspections. Maintenance has to come from an authorised shore based facility, which means authorised and trained technicians.

Let us see how they fare. Or will they snag when deployed, due to the size?

IN CONCLUDING

How would I rate the whole gamut of Life Saving Equipment over the ages on a scale of 1 to 10?

9.5 for Life Rafts, the -0.5 going away due to the fact you will have to go down to the water to board the deployed boat. Also, once deployed it needs to go to an authorised service provider for re-installation.

9.0 for a Single Fall Capsule Type of Lifeboat, the -1.0 taken away for its dependence on a powered crane.

8.0 for a “Free Fall” Lifeboat, the -2.0 going away due to possibility of sticking on the guideway and the chances of injury to limbs and loss of life due to the increase in G-forces during the drop. Added possibility of somesaulting after she surfaces from the water.

7.5 for an Enclosed Life Boat with plain hooks, the -2.5 going away towards probability of falls corroding and breaking, falls twisting and getting the boat stuck midway, centrifugal brake problems.

5.0 for an Enclosed Life Boat with Modified Hooks, the -5.0 going away for the cam of the hooks failing at intervals, causing accidents and loss of lives and also towards probability of falls corroding and breaking, falls twisting and getting the boat stuck midway, centrifugal brake problems.

AR

Amigo Tyres is a Rocklea based store that supports truckers, families, and businesses with tyre replacement, repair, and truck mobile services in Rocklea. Visit the best Rocklea shop for truck tyres and services! Visit: https://amigotyres.com.au/services/truck-wash-service-in-rocklea