Blog 88 - "Bernardo Quintana" - Self Unloader Work Aspects - 'Training' a Belt

- ranganathanblog

- Nov 6, 2022

- 13 min read

A Shakesperean dilemma - Do I watch the World Cup (T20) or send out my blog?

Netherlands just now beat South Africa, denying the latter a Semi Final berth.

India are through to the Semi Finals by virtue of South Africa's defeat.

Pakistan and Bangladesh are clashing in a 'do-or-die' meeting.

Marine Musings 25 - Converted to a Self Unloader - Named “Bernardo Quintana” - Nearly Two Months Spent in the Yard Overseeing the Final Stages of the Conversion to a Self Unloader - Sailing from Ulsan to the US Gulf

2 Months in the ShipYard :

Everything went off well. All tests were performed to satisfaction.

All Self Unloading Equipment were tested out and a few, small adjustments made. My experience of the “Citadel Hill” came to be of immense help during this shipyard stay.

For the first time, two new computers came on board, loaded with MS Word and Lotus 123. I spent all my spare time learning all aspects. Lotus 123 proved to be particularly good and my favourite.

At the end of the conversion, I do not know why the Superintendent and Vulica skimped on not painting the ship. Penny wise and pound foolish - the in charge Superintendent from Barber's as well as the Vulica representative were certainly capable of such decisions.

Voyage across the Pacific to Los Angeles for Bunkers, Stores and Provisions

We left Ulsan with a task given to us - paint the ship and make it look good for the naming ceremony. The Pacific crossing was not all that smooth with many a day spent shipping sea sprays, so that preparing a surface and painting it became well nigh impossible. This was conveyed to the Owners. Why they had skimped on doing this in the ship yard itself was beyond my comprehension.

The Owners, Vulica, were very upset with the Captain. They sent a team of 2 experts from Jotun Paints to help expedite the painting work - they joined us at Los Angeles. By the time we coasted down, went through the Panama Canal and went up north into Punto Vinado in Mexico, a total of 2 hatch covers had been grit blasted, washed with fresh water, cleaned with chemical and painted with the standard number of coats, under the expert eyes of the Jotun people.

By the time we reached the Panama Canal, there was panic in the Office, panic from the Owners, panic from Jotun, as the ‘christening’ ceremony had now been advertised and a few hundred VIPs were expected to attend. Quietly, from then on, we just resorted to slapping paint on anything that did not move on deck and greased anything that did. Like badly made roads where potholes would show up within a week or at the first signs of rain, this kind of painting lasted for a couple of weeks after the ceremony.

Being weather free, the Engine Room had been cleaned and painted.

Before reaching Punto Vinado, Mexico, we were asked to design a rig that would carry a bottle of champagne that would smash on the hull of the forecastle, when a ribbon was cut about 30 metres away. Design it we did; the bottle smashed, the champagne spilled on the hull and the vessel was christened ‘Bernardo Quintana’, named after a Mexican civil engineer.

Unfortunately, the Owners did not take the Captain’s responses about painting of the ship kindly and asked that he be relieved. He was sacked for no fault of his own.

The ceremony was exclusively a Mexican Charterers’ - US Owners affair, where the ship’s staff was relegated to serving duties when the shore party boarded the vessel. I also fell afoul of the Owner’s representative when I objected to the crew and officers being used as waiters, where I clearly stated that we wouldn’t mind guiding the guests through the ship but would not serve as waiters. The implication was “So, sack me too”.

The advantage that a “Self Unloader” offered an Owner or Charterer is the ease with which bulk cargo can be discharged. The simplest method for discharging the cargo was to tie up the ship to a jetty, swing or extend the boom, start the Self Unloader plant and run the belts, open the gates as preplanned and discharge all cargo to form an open pile.

The second - slower - method is to discharge the cargo into a hopper, with a conveyor belt at the bottom to take away the cargo as it accumulates in the hopper.

An even slower process is to have trucks come under the hopper to take away the cargo.

On a one-off trip to the Bermudas, we have had occasion to tie the ship to several trees ashore, as there were no other facilities. We completed discharging cargo in that manner, without incident.

The Bernardo’s plant capacity was 8000 tons per hour, a veritable waterfall that flows out of the boom belt. During my stay, we were allowed to go to full discharge capacity only on three occasions.

On one such occasion, a passing ship staffed by Barber staff called me on the hand radio and the Captain, who I knew well, said “My God Bada Saab, what a sight. I’ll never forget this. It is a beautiful wterfall”.

On another occasion, the port had given permission to discharge into an open ground. Even though the cargo was widely spread by either raising the boom or slewing the boom, the whole space collapsed and caved into the water.

During a lull in the influx of cargo that was coming into Punto Vinado, the Owners decided that the vessel should carry grain from a US port to Italy. The plan was a 14 day trip to Italy, a 2 day discharge and a 14 day voyage back to Punto Vinado.

The problem was the logistics and support system at the receiving end, as they did not have the facilities to carry away the grain as fast as we could discharge it. We would start the plant at 9am, swing the boom out to the maximum reach and discharge on to the concreted quay. The Port would ask us to stop by 11 am and would spend the rest of the day and the night to clear the cargo.

The entire town would stop work and watch the flow of cargo from the conveyor, the Italians famed for being distracted with such diversions.

For us, it was a time of peace and quiet for a month.

Instead of a month, the voyage up and down took nearly 2 ½ months, causing a loss to the Owners of about five loadings at Punta Vinado.

Factually, there is not much to write about this ship, except for the fact that, being a self unloader, it squeezed the life out of me, but not to the extent that the "Citadel Hill" had done.

The work on the self unloader plant was very repetitive and very, very, physical. Absolutely nothing cerebral. Just donkey work.

What Happens on a Self Unloader

CLEANING AFTER DISCHARGE:

In a 5 or 6 day cycle, a discharge would take place in a US Port, mostly Houston. On completion of discharge, the self unloader staff and the deck crew would rest up and start work the next morning. This included the Chief Officer and myself.

First would come the washing of all the holds right up to the hydraulic gates by the deck crew, starting from # 1 Hold. This water would fall on to the belts and overflow on to the tunnel floor.

The tunnel staff would start washing the tunnel timed to be slightly behind the deck crew, starting from the forward end. Using salt water to wash the tunnel was detrimental to the steel structure supporting the belts, but could not be avoided as the amount of fresh water needed to wash the entire would have been prohibitive.

I initiated a compromise by first washing with sea water, with another person rinsing all the steel structure with fresh water, to minimise corrosion.

As remnants of the cargo would fall on to the belts along with the wash water, the belts would be overloaded. By inching the tunnel belts, using the load control hydraulic pumps, we would transfer the remnants of the cargo on to the transfer belt, take it up by the loop belt and collect it on to the boom belt.

The water on the tunnel belts would fall away when it reached the transfer belts. A slurry pump at the aft end of the tunnel would take care of the disposal of accumulated water.

After the second such discharge of the same grade of cargo of gypsum, I suggested a ‘brushing down’ of holds of cargo remnants which would fall on to the tunnel belts. This would then be sent to the boom belt to be kept for discharge at the load port.

This way, our self unloader structure would be saved from the ravages of sea water corrosion from washing.

Any cargo that had spilled on to the tunnel floor or had gone under the belts, would be brushed or swept, collected and put on to the belts. After a few weeks of this ‘brushing’ and ‘sweeping’ I asked for, and received, 2 large sized Industrial Vacuum Cleaners, which speeded up the process all the way.

MAINTENANCE, ONCE THE WASHING AND CLEANING WAS OVER:

Once the ship was in the load port, the boom belt would be run to discharge all the remnants of cargo that had been collected from all over, which had been sent to the boom belt.

During every discharge operation, a constant to-do list would be maintained of observations on faults that were observed or likely to take place. This included rollers that were too noisy - indicating bearing damage, hydraulic valves that were leaking, gates that were troublesome to open or shut, belts that needed to be ‘trained’ (not running centrally - tending to go to the edges), pedestal bearings that were running hot, electric motors condition and many other observations.

These were, then, listed and prioritised. Work on these would start as soon as the washing was over, sometimes overlapping with the washing.

Being a new ship with new self unloader equipment, there were not many jobs that would come up, so we would spend the remaining time in upgrading the tunnel itself, mainly with the application of anti corrosive paints. Because of the nature of the cargo and the use of salt water for washing, the steel used in the plant deteriorates fast. The intention was to identify those areas and maintain them properly from day one, rather than wait a year and start maintenance after seeing signs of deterioration.

“Training of Belts”

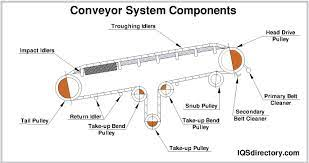

Example of the Components of an Endless Belt

The Belt is kept under tension with the 'Take-up Pulley', the ends of the pulley being connected to two hydraulic cylinders under adjustable oil pressure, to vary the tension for different cargoes, if necessary.

Work on a ‘Self Unloader’ is mostly repetitive and involves a lot of donkey work. A lot of experience is required and a lot of thought needs to go into the ‘training’ of belts. Without a holistic view, if one were to make adjustments to pulleys or idlers or rollers, a whole new set of unwanted results may start appearing. When I initially started ‘training’ conveyor belts on the ‘Citadel Hill’, I made the mistake of not noting down what I had done at each step of the alignment. After running around in circles for some time, better sense prevailed and a more organised, structured approach was used to correct matters. It was a lesson that was learned the hard way.

All the belts, whether new or old, needed to be ‘trained’ constantly. The ideal is to have a conveyor belt run exactly centralised, in a straight line from point A to point B, whether it is loaded with cargo or running idly. When passing over various pulleys, it should continue to remain centralised - ideally.

In actuality, the belt, when running, meanders along, first going one way and then another, dependent on many factors like how the cargo is distributed on the conveyor belt, the different elongation or stretch of the belt at different sections, the (very slight) inclination of a pulley or idler or roller which can make the belt move one way or another across the surface. Even worn out slots of the pedestal for the angled rollers (used to 'trough' the belt) can cause waywardness of the belt, as the angle of the roller changes.

Allowing the belt to run as it will can have a variety of impacts on the plant, mainly on the conveyor belts. The conveyor belt(s) are (almost) the costliest single pieces of equipment in a Self Unloader Plant, needing to be protected from damage as much as possible, to ensure longevity of service.

Image of belts of the plant

The whole plant looks pretty complicated, but once one understands the concept in its entirety and visualising the flow pattern, it simplifies itself into 4 simple parts.

The tunnel belts - 2 on the Bernardo, 3 on the drawing above (#4) - are the smallest in width (in comparison to those that follow) - I think it was 90 inches, but am not sure, possibly 7 or 8 plies constituting a thickness of about 1 ½” - and had the lowest of speeds (in comparison to those that follow).

From the forward end of the ship they run on a raised structure, practically parallel to the tunnel floor until the last 10%, where it is inclined upwards, the inclination just enough to allow the cargo to drop into a hopper. All this while the belt has been running in a troughed structure, akin to the cup shape of a longitudinally cut pipe. There are a series of three rollers to help ‘trough’ the belt, the middle horizontal roller and the 2 side rollers, inclined to 22 ½ degrees.

Once the cargo on the tunnel belt gets discharged into the transfer hopper, the belt, being a continuous one, runs below the roller’s structure and is guided back to the head pulley by return rollers.

The Transfer Belts are inclined upwards and run towards midship, discharging in to a hopper that spreads the cargo on to the Inner Loop Belt.

When the Inner and Outer Loop Belts come together, their respective tensions sandwich the cargo between the two belts. Running in a vertical arc, the sandwiched cargo in the Loop Belts carry the cargo almost vertically for about 30 metres and discharges onto the Boom Belt, which then discharges the cargo ashore.

In order to prevent any ‘choke’ points, each belt runs a little faster than its predecessor. The Tunnel Belts speed is the minimum. The Transfer Belts speeds are a little more. The Loop Belts speed is more than the previous ones. The fastest is the Boom Belt.

Even a slight misalignment at one of the roller carriers or an idler pulley or the main pulley or the ‘take up’ pulley can have a slowly increasing effect over the full length of travel of the belt.

In a worst case scenario the belt rides up one side of the ‘trough’ provided by the 22 ½ degree tilted side rollers, at which time the edge of the belt comes in contact with the ‘side rollers’ and keeps rubbing on the side roller. After a while, the edge of the belt becomes hot due to the friction caused.

The less dangerous result is the splitting or opening of the plies of rubber. Not noticing this in time and rectifying it can cause the belt edge to split open, which progressively increases the damage as time goes by.

The more dangerous aspect of such a run is the belt can catch fire due to the friction and quickly spread.

So, proper ‘troughing’ and ‘middling’ of the belt is dealt with care.

Although, at first, it takes time to align and ‘train’ a belt, one soon becomes an expert by a matter of constant observation. A walk by the side of the running belt and keeping track of where it rides ‘high’ or is not centralised on the pulleys gives one the basics of where to start.

It may mean a minute more inclination given to a pulley, by adjusting the bearing bases. It may mean just one of the ‘troughing’ rollers is out of alignment.

After a while, one starts to enjoy the skill that goes into identifying the exact spot which is out of alignment.

The importance of keeping the belts controlled is best demonstrated by the Marine Report of a massive fire that took place on the “Ambassador”, which report I will copy and paste in my next blog.

Different cargoes impact the Self Unloader Plant in different ways.

If the cargo is dusty and of fine powder, apart from being a health hazard, enters the bearings, whether large or small, whether ball bearings or roller bearings or pillow block bearings and, after a while, prevents the bearing from working. The only part-solution to this is to ensure all bearings are sealed properly.

If the cargo is lumpy, like rock phosphate, one can expect belt damage, all the belts being vulnerable to this damage. Constant repairs to the belt is the only solution, till the damage exceeds certain limits at which time it may be necessary to renew the entire belt.

One of the most difficult cargoes that a Self Unloader Plant has to discharge is rounded steel pellets, almost like marbles. As this cargo starts moving up the loop belt, being rounded, it does not stay on the belt and starts sliding down. So the discharge has to be limited in quantity and the loop belt tensions increased.

Soft and powdery cargoes create a problem of their own. Firstly, they are a health hazard to those who have to necessarily be in the vicinity. Paper masks will not do. I ensured that a sufficient supply of special filtering masks (from Unitor) were always available.

‘Hang ups’ were a problem, where the cargo gets stuck to the holds and would not come down, unless dislodged using either vibrators or manually, using long rods with scrapers at their ends.

It is the Chief Officer and his crew who are responsible for ensuring these ‘hang ups’ are brought down to the running belts. I had an occasion where a Chief Officer and Master sat in the Master’s cabin and planned out what the Chief Engineer must do and how he must get the stuck cargo down. Then they called me to tell me what they had decided and what they expected me to do. After listening patiently, I politely told them “So far, I went beyond the call of duty in assisting in areas where you were finding it difficult and solving all your problems. That stops as of now. The belts will be running, the gates will be operated. If no cargo falls on to the belt, so be it. If you are not able to get the cargo to the belt, so be it which, any way cannot be done with both of you sitting in your office and planning what I should be doing, instead of planning what you should be doing.”

The Captain then said that he will be talking to the Office about my attitude. My reply was to tell him to “go ahead, at least then I do not have to sail with such moronic people”.

The call was immediately made. They both were roundly chastised for not knowing what their duties were on a Self Unloader and to get cracking to get the cargo on to the belts.

This ship was, perhaps, one of the few ships that I went through a full tenure without problems. Being the first Chief Engineer after the conversion, I had to set the bar for others to follow. As the weeks went by ‘Instructions’ were chronicled in detail on almost all aspects of ‘Self Unloader’ work, the instructions tending into a thick file.

Even today, nearly 30 years down the line, I cannot account for the 10 months I spent on board. Time just flew.

I signed off the ship in March 1993 with the assurance that my next ship would also be a Vulica Self Unloader ‘Blount’, in spite of my being at loggerheads with the Vulica representative.

===== "Marine Musings 25" Continues - Blog 89 next =====

Comments