Blog 66 - A "Concorde" Take Off and a Bulk Carrier "Talabot" Take On (from Norwegians)

- ranganathanblog

- Aug 21, 2022

- 12 min read

Updated: Sep 11, 2022

Marine Musings 18 - Talabot – Tenure from 19th Aug 1984 to 07th March 1985 (as per Articles)

Foreword:

Once in a while, I receive comments on one or the other of the previous Blogs, triggered by the similarity of the occurrences or events.

In the last week, I received some - more than usual. I will quote them verbatim, taking them one at a time. Here is the first one, in consonance with Blog 65, on the anchor 'running away' and the bulbous bow.

Quote

Hi Rangan,

Here we go again on parallel tracks.

Had the starboard anchor chain slip out to the bitter end in very bad weather on a voyage from St.John’s New Brunswick.

I was the Ch.Off on departure stations forward with pilot on board as was the practice in those days.

Before leaving forward stations I was to ensure that both the anchors were properly housed and the anchor cables properly secured.

It was bitterly cold, visibility was poor and there were patches of fog. The tidal currents in this area has been the cause of grief to many a mariner.

It was no surprise that the Master was nervous and wanted some more help with the navigation under these circumstances.

He asked me to leave the securing to the Carpenter and report on the bridge.

I left forward stations and reached the bridge about the same time as the pilot was disembarking.

We dropped the pilot safely and negotiated the shoals and were now in deeper waters heading for the Atlantic where some pretty bad weather awaited us. Carpenter reported that both anchors were secured but I did not go forward to check if this was done properly.

It was our maiden voyage on a new class of ship. Slightly larger and around 16,000 tons dwt.

She was slamming quite heavily into head seas.

The next morning it had moderated sufficiently for the carpenter to take his soundings. When he went forward he noticed the starboard anchor lashings had given way and when he looked over the side the anchor cable was leading astern downwards. All the cable had paid out and it was hanging in there perilously at the bitter end. I am pretty sure had I secured these anchors this would not have happened. No sense pointing fingers.

We needed to get the anchor and cables back where it belonged. Weather was still bad and if we stopped we would end up beam to sea and swell and that was out of the question. Took additional lashings so that even if the bitter end gave way we would have these heavy lashings to fall back on.

Speed was reduced to half ahead and we continued heading for Gibraltar. The next day the winds had died down and the danger of ending up beam to the sea ans swell was not there. We stopped her dead in the water till the cable was pointing straight down.

The Chief Engineer Russi Bhathena, one of the finest person you could come across and a dear friend to me besides was there. Hardly had we reeled in a few links when the fuse blew. We had just four fuses. We had to think of some other way. We could use our Jumbo derrick and haul in the chain some twenty feet at a time. It would be a very tedious process but there seemed no way out. Then out of the blue it struck me to start heaving when the bow was on a downward dive and stop when the bow was on the rise. It needed to be done while we still had this swell. I took the windlass controls with Ch. Eng in attendance . Wonder of wonders it worked and at the rate of few links each dive we got in a few shackles when the motor started getting too hot for comfort. We waited for about an hour or so for it to cool down and resumed till we had about six shackles out. At this point I felt the windlass would be able to pick it up and I continued heaving it in even on the rise. She groaned but continued to reel in the shackles till it was all in. I thanked my God for helping me with this idea that worked as opposed to the tedious use of the Jumbo. One more fuse blew in the process but the Anchor and cables were back where they belonged and we were back to full speed homeward bound. That was one of the many nightmares I could have done without but at the end of the day these happenings are what defines you. For the better or worse.

You are also correct about seniors not paying much attention to training of the youngsters. I carried all my Dufferin notes with me and cadets had to report to me at 0600 sharp. Penalty was one hour of extra work for each minute they reported late. After the first few mishaps they were there on time every time. I used to give them the days work but till breakfast they could copy my notes or spend time studying, make their own notes and ask me anything they did not understand. It was well appreciated by the cadets though I worked them hard. After all it was for their better understanding of the subjects that mattered at sea. The greater your understanding, the greater their chances of survival.

Then your observations of the Bulbous bow once you understood the theory was the natural way to go provided you were able to achieve it.

I had noticed even if you were head down with a bulbous bow you made better speed provided you got the bulb submerged just right.

This as opposed to the theory of being a few feet by the stern was the best before the bulbous came into the picture.

Best regards,

Bobbie.

Unquote

Chapter 1 – I Fly to Paranagua as Advance Party to Take Over the Talabot from Norwegians

As usual, I flew from Chennai to Mumbai to complete all formalities. I was given a rather large file to peruse later. I was told I was going as advance party, along with a Chief Officer, to take over a Wilhelmsen bulk carrier, MV Talabot, from the Norwegians and prepare the vessel for take over by Barber Ship Management somewhere in Europe, dates to be fixed later. The ship was to berth at Paranagua in Brazil and both of us were to join before she sails.

We then flew Air France on what was one of the longest flights for me. We had a stop over at Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris of about 14 hours, before the next flight to Brazil.

Flight time from Mumbai to Paris 10 hours + 14 hours stop over + 12 hours to Sao Paulo + 6 hours drive to the ship

Courtesy Fly4free – Mumbai to Paris Flight Time 10 Hours

While at Charles de Gaulle air port during the stop over, an Air France ‘Concorde’ was parked just outside where we were sitting and, later, we had the pleasure of seeing her take off. If aeroplanes can compete in “Miss World” pageants, the “Concorde’ would be the permanent winner. Such grace, such beauty – I was lucky to see her just outside, on the other side of the glass and, later, watched her take off. Our flight, to our regret, was not the ‘Concorde’.

Courtesy Fly4free – Paris to Sao Paulo Flight time 12 hours

Sao Paulo to Paranagua – Drive 6 hours

The vessel had just completed loading when we reached and boarded. It was touch and go, but I, later on, found that they had gone slow with the loading so we could reach the ship.

The ship, ‘Talabot’ was a scaled up version of the ‘Willine Tysla’ and was part of the series of 6 ships built in the Tsu Yard in Japan, all six of them carrying successive Hull Numbers. The difference was she was a bulk carrier, had no cargo gear on deck, had side rolling hatches and with larger Engine Room and accommodation spaces.

Beautiful accommodation, Master and Chief Engineer cabins with massive bay windows, well designed and well equipped entertainment equipment of the day, a modern, large galley and a movie room with a 16 mm projector, with latest movie reels from a Norwegian source, later changed to Walport.

Try as I might, I have not come across any photograph of the ‘Talabot’.

I was seeing, for the second time, side rolling hatches, operated by a motor – chain combination with hydraulic jacks. I was seeing, for the second time, a deck that was devoid of cargo gear. (The "Chennai Muyarchi" was the first).

As I had experienced and witnessed before on the ‘Trianon’, there was no cooperation from the Norwegians. The First Engineer was the only one who was tolerably friendly in the beginning. I resigned myself to spending the next 27 days without any cooperation.

But, every tale has its twists - so did mine.

We were on a long voyage of about 27 days, carrying iron ore to France, from approximately 25 degrees South of the Equator to about 43 degrees North of the Equator, from the South Atlantic Ocean through the North Atlantic Ocean. (25.5201° S, 48.5099° W to 43.4379° N, 4.9457° E). A long voyage for a takeover, with a relatively unfriendly crowd. Unfriendly because we were taking away their jobs. They also gave many indications that we were not their equal in terms of professionalism.

Chapter 2 – How I got the Norwegians to my Side

THE FIRST WEDGE INTO THEIR WALL OF INDIFFERENCE

Now, I was on a ship that was the sister of “Tysla” in most aspects, having been built in the same shipyard. Hence, I was pretty familiar with the layout. Added to that, having served on bulk carriers earlier, I quickly became familiar with the ballast lines. The Main Engine was a larger version, the Engine Room lay out mostly the same and I quickly felt at home. I am unable to recollect if the ship had 3 or 4 generators.

Two days had passed and I was only a tolerated presence in the Engine Room. It really did not bother me, but I needed their assistance in one very important aspect – that of Flag Change inspections – which co-operation did not seem likely.

On the second afternoon at sea, they had a generator problem, where the generator was tripping off the Main Switch Board. Their Chief Engineer, Electrician and First Engineer worked on it, pouring over circuit diagrams that evening and well into the next day. About 3 PM the next day they gave up. Their Chief Engineer told me ‘Don’t worry, we’ll get it fixed at the next port before we hand over’ and he went up, along with the Electrician.

The circuit diagrams were still spread out on the Engine Control Room table, so I started looking at them. Although I was never good at circuit diagrams, I found that I understood the circuit as it was exactly the same as on the ‘Tysla’, when we had a similar problem of the generator not staying on load.

I asked the First Engineer if I could try to solve the problem. He said I was welcome to try, but in a condescending way, like ‘what can this guy do that we couldn’t’ sort of expression.. I once again checked the circuit diagram, asked for a stopwatch, asked him to start the generator and try putting it on load. With the stopwatch, I determined that the trip occurred exactly at 10 seconds. I checked the setting on the dials of timers inside the switch board, saw (Omron) Timer T3 was set to 10 seconds, reset the timer by bringing it to ‘0’ and again setting it back to 10 seconds.

I, then, asked the First Engineer to once again try to load the generator. It did not trip. The First Engineer kept saying “It will trip now, it will trip now …” and, after five minutes of the generator running normally, he reluctantly agreed that the problem had been solved. He called the Chief Engineer and Electrician down and they stopped and started the generator, put it on load and took it off load again and again, expecting it to fail, hoping it would fail. But, like the ‘Duracell’ battery it kept going and going.

I, of course, had resorted to a bit of subterfuge and did not tell them that I had faced the very same problem on my last ship, where I had an excellent Electrician to diagnose and solve the problem.

This solving of the problem got around. The evening dinner table was a rather silent affair, where, before, it had been rather animated, with some asides thrown in my direction in their own language which, at any rate, was not difficult to comprehend.

PROBLEM WITH ONE ‘FRIDGE COMPRESSOR

Their First Engineer was the first one to openly say that I had sorted out a problem that they had given up on and there was no questioning the professionalism and knowledge of the Indian Chief Engineer. He, then, opened up and said “Chief, there are other problems that we are having, which we have not been able to solve. Can you help?” I said ‘Sure’ and we became close friends for the remainder of the voyage, with him arguing on my behalf when there was the slightest slur on me.

The first problem that he told me about was that of the ‘Fridge Compressor. When I told him I had suspected it and he asked me how I did know, I showed him the ‘Fridge Compressor Spares locker. They were carrying 4 crankshafts, 8 pistons, 4 sets of bearings, 4 connecting rods and enough spares to build 4 compressors. That indicated a severe problem, as no ship carries spare crankshafts and so much of other spares.

Co-incidentally, the ‘Fridge Compressor that was the problematic one failed again the next morning. As per records, it had been failing at least twice a year, for the last 4 years.

I had noted on the preceding two days that the Lubricating Oil Pressure was low.

In ‘Fridge Compressors, there are three gauges to help you with your diagnosis on operating conditions – Suction Pressure gauge, Discharge Pressure gauge and Lubricating Oil Pressure gauge. The construction of these compressors is such that pressure inside the crankcase is equal to the suction pressure of the refrigerant gas. This suction pressure is acting on the oil in the crankcase. This oil is drawn from the crankcase by the attached oil pump, pressurised and sent into the bore holes of the crankshaft to lubricate the main bearings, bottom end bearings and, through bore holes in the connecting rods, to the gudgeon pins, the oil then falling back into the crankcase, some of the oil coating the liner and assisting in the cylinder lubrication. The cylinder liner is also lubricated by the splashing of the oil when the crank bearings rotate.

Since the suction pressure acts on the crankcase oil, the initial inlet pressure to the lubricating oil pump is equal to the suction pressure of the compressor. Then the pump increases the pressure, normally by about 1 kg/cm2. So, if the suction pressure gauge shows 0.8 kg/cm2, the Lub Oil Pressure gauge must show at least 1.8 kg/cm2, if not more, for proper lubrication of the bearings. This had been showing only about 0.2 kg/cm2 more than the suction pressure, which meant the bearings were not receiving pressurised lubricating oil. This was what was damaging the compressor.

The 1st Engineer, the Fitter and I opened the compressor completely. The crank pins were scored badly enough to need renewal of the crankshaft, the bottom end, top end and main bearings were damaged, the pistons scored, the rings seized up, and connecting rods slightly bent.

I concentrated on the Lubricating Oil Pump and the bore holes in the crankshaft and connecting rods.

The new crankshaft and connecting rods were fine, the oil bore holes clear. The following three diagrams show how the pump works, with the fourth showing oil flow. I just sat on a stool at the site of the compressor and kept imagining every single thing that happens and tried to visualise it. It took me a while to find the fault.

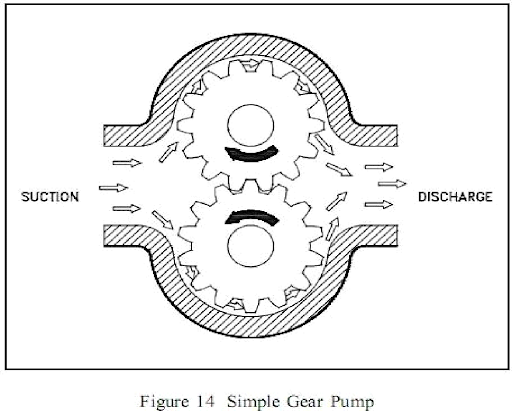

If one looks at the internals of the pump, there are 2 gears, one the driver – which is an extension attached to the crankshaft – and the other is the driven. If the driver rotates clockwise, it will send the oil from the suction side around the periphery of the volute casing, to be discharged on the other side at a higher pressure. Meanwhile the driven gear also does the same thing to the oil, but rotates anti-clockwise. The oil going around the periphery is what pressurises the oil.

My thoughts went in a different direction. What if the driver gear rotated in an anti-clockwise direction and the driven gear in the clockwise direction? The oil would then pass through two or three gear teeth and practically get connected from the suction side to the discharge side without going around the periphery of the volute casing, thus building up very little pressure.

Next query – what would make the pump rotate in the opposite direction? If the pump was rotating in the opposite direction, the crankshaft was rotating in the opposite direction. The compression would not be affected, because all that the piston had to do was move up and down for compression to take place.

What made the crankshaft rotate? On the end opposite to the lub oil pump is a pulley that is pressed on to a conical face and has a nut with washer. A 440 volt motor rotates the shaft by means of belts, motor pulley to compressor pulley. What can go wrong?

The next morning I was up early, as usual, when I had my ‘Eureka’ moment. A 440 volt motor can rotate either clockwise or anticlockwise depending on how it is connected to the terminals. When we went down and completed assembling the compressor, we tried it out and found the lubricating oil pressure was much lower than the gas suction pressure, which it should not be. Then I asked the 1st Engineer to open the terminal box and reverse connect two terminals. The lubricating oil pressure shot up to 2.2 kg/cm2, which was about normal for this compressor. Problem solved.

It was likely that, 4 years ago when the motor was overhauled - as per their records - and bearings changed, the Electrician had, initially, not marked the position of the terminals and had connected it wrongly after overhaul, thus changing the direction of rotation.

===== Continued in Blog 67 =====

Comments