BLOG 46 - "Marine Musings 12" - We take over the "Trianon" at Kuwait Anchorage

- ranganathanblog

- Jun 12, 2022

- 16 min read

It was a time of the perils. We were contending with machinery that were on the point of a breakdown. If anything were to breakdown now, we would be accused of lack of expertise in operating machinery and sniggered at. The next seven days were crucial. Our professional reputation was at stake. Added to the machinery being in such a state, the new staff were inexperienced and had to be shown almost everything. I hardly left the Engine Room for the next seven days. To their credit, the new staff also gave all their hours for overhauls and familiarisation. I respected them for that and, in return, taught them all I knew over the course of the year that I was on board.

Chapter 2 – The Transfer – Our Staff get Familiar with the Ship – I Confront the Chief Engineer – Generators’ and Purifiers’ Overhaul on a War Footing

The transfer took place smoothly on 8th July 1977 at Kuwait anchorage. For a period of about 3 hours, the new Chief Officer, the Norwegian Captain and myself were the only ones on board, the Norwegian Captain having stayed back to hand over the safe keys and combination and the contents of the safe, which contained money and scheduled drugs that have to be kept under lock and key, as per WHO guidelines.

Usually before the change of Registry – or Flag change – the new Flag Inspector or Surveyor from the Port of Registry will board the ship and inspect it to ensure the ship conforms to the country’s laws. Singapore was then considered a Flag of Convenience, so no such sort of thing happened. The old Captain lowered his country’s flag (Norwegian) and the new Captain raised the Singapore flag and that was that.

After our own staff boarded and settled down, we had to conduct mandatory mock life boat drills and mock fire drills, so that everyone knew their stations, responsibilities, where emergency equipment were stored, how to sound the alarm in case of emergency and other safety details. The Chief Engineer was the designated Fire Chief. I assisted him in going through all the drills, as I was familiar with the layout.

From the time they boarded, it was 6 hours before we started engines and started our voyage.

From the start, I liked the ship, the staff, the atmosphere and I thrived in it. I had a relatively inexperienced Third Engineer, a totally inexperienced 4th Engineer and one 5th Engineer who was brand new. The number of Engine Room staff had reduced quite considerably, as also the total number of personnel on board. We now had a total complement of 28 on board, compared to the 50+ we had in SISCO. It meant more work for less people. Besides that, the inexperience of the other Engineers meant that I had to show them and teach them.

Because of the extreme conditions the generators were working under, my first priority was to prevent a breakdown of the generators. These were all 6 cylindered B&W generators. We worked almost non-stop for 3 days and got the defective generator ready. The condition of the cylinder heads, pistons, piston rings, coolers, turbocharger were appalling. Luckily the bottom end and main bearings were good, so we could complete the job quickly. We also had 5 overhauled cylinder heads kept by the previous staff, with one already on the defective generator. The piston that was forced in was removed with difficulty. Why did the piston not go in when the Norwegians put it in? The piston was brand new and the groove heights were lesser than worn pistons. There were different sizes of piston rings in stock. The right one needed to be chosen which would give a reasonable axial clearance, after which the piston went in smoothly.

The air inlet passages of the removed cylinder heads were 95% choked with carbon. Valves were badly pitted. The pistons were heavily carbonised and most rings nearly stuck. Turbochargers were running at 50% of the speed that they were meant to run, because of heavy carbon on the blades and worn bearings. Coolers were choked. Luckily we had plenty of spares.

One group would work on the generator engine and another would decarbonise and overhaul the removed parts.. Those on the engine would clean the parts, calibrate them and assemble them on the generator, as and when they were ready. The Fitter and crew knew what they were doing. The Electrical Officer also pitched in. I guided all of them every step of the way, as I had the experience of overhauling generators singly from my 4th Engineer days, with only 2 wipers to assist me.

One generator done.

Two generators were needed for out-at-sea running, to provide power to running machinery. The second generator was opened up and overhauled. This was completed in 2 ½ days. Now the exhaust temperatures were reasonable but still a little high at 330 degrees to 350 degrees, but they were now running at least 300 degrees lesser than before. I taught the engineers how to adjust fuel timing and, after it was carefully done, the temperatures came down to around 280 degree, which was standard at that power production.

We needed a third generator to be running during port manoeuvres, which was also ready in 3 days. By the time we reached Singapore, 3 generators were back to normal operation. The 4th was also completed after we left Singapore.

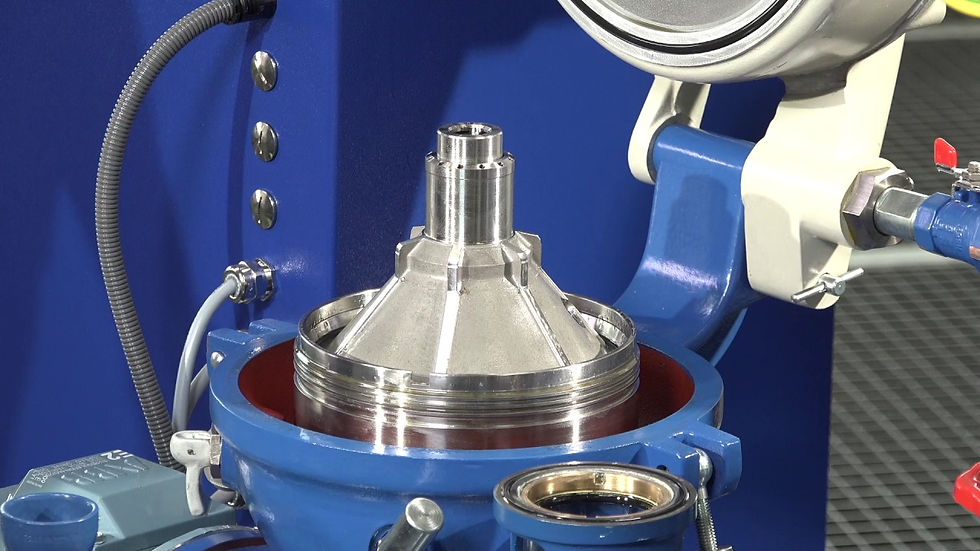

Simultaneously the Alfa-Laval purifiers were also overhauled.

You Tube : A Dirty Purifier

From You Tube : A dismantled Purifier

Courtesy You Tube : A New Purifier with Cover Open

There were other legacies left by the previous staff. Some Main Engine exhaust valves had not been changed and were overdue. Fuel injectors were overdue. Scavenge space drains were all choked and spaces required cleaning. Air coolers’ air sides were running at high differentials. The exhaust boiler was heavily carbonised and had to be cleaned urgently to prevent an uptake fire. Auxiliary boiler tubes were choked. Day by day, we found more and more work needed to be done to improve the plant.

The Chief Engineer was the most experienced person I have ever sailed with, Mr. Remedios. He had started his working life as an aircraft mechanic, then joined the Merchant Navy and moved up the ranks. He was an irascible, no-nonsense, hard working type. He used to come down every day and work with anyone who was doing any job.

The problem was he used to get annoyed if the person he was working with was doing what he thought was a shoddy job and shout at him. Within 3 days, almost all had got a tongue lashing from him and used to literally shake in his presence. The morale of the staff was down right in the beginning of the contract. I had to do something. I could understand his wanting to keep busy by working in the Engine Room, but he was completely shattering what should be a smooth process of working in an Engine Room. His favourite victim was the 3rd Engineer, who was a total wreck within a week. It was not that he was intimidating. He was exasperating, due to which I was not able to get any productive work out of my staff. Meanwhile, he had managed to incense the deck staff and also the Captain. His tirades used to unnerve everyone and keep them nonplussed.

I confronted him. I explained that his presence in the Engine Room was detrimental to the smooth functioning of the Engine Room and he had managed, within hardly a week, to make a mental wreck of the 3rd Engineer. Although he was more than 20 years my senior in age, I boldly spoke to him like a Dutch Uncle. I gave him other options – I would consult him on the planning of work, methodology of doing each job correctly, report to him and ask for his advice if I had problems and, finally, at the end of each day, give him a detailed analytical report. This included deck machinery work, the Electrician’s work and any other work I may have done. I told him that once every week he can come down to the Engine Room, take a round, inspect, make his notes of deficiencies and talk to me only. I also told him that I have been very honest in my job since the beginning 7 years ago and I will continue to maintain that same honesty. I continued with a proposal to him that if I do not come up to his expectations or match his standards within 10 days, he can either involve himself in Engine Room work or sack me. All this took place very calmly.

At first he was aghast. He told me later that no one had spoken to him in this manner or stood up to him. In a way he was bemused but he saw the logic in what I said. He said “Okay, I won’t disturb you” and left it at that. I had already realised the basic goodness in him. His weakness was that he expected to see that everyone was as good as him. If not, he lost his temper. Ship after ship, he had made himself very unpopular. The Company had received several complaints about his anger but, as he was a top class engineer, looked the other way. But he had never fired anyone from his job.

It was after this that the Engine Room became a joyous place to work. The ship was a 19 year old ship with a slightly more advanced B&W Engine. All machinery were of good quality, sturdy and robust, but their maintenance schedule had not been kept up for nearly a year, as the previous staff knew about the transfer quite a while ago and had not bothered to do any work except to clean and paint the floor plates and machinery.

A week of having been on the ship allowed all the staff the cushion of time necessary to familiarise themselves with their routine duties. Since we were quite behind in running maintenance, after completion of generator work, I called the staff and gave them 2 options: First option was to spread all pending maintenance work over the full 12 month period of the contract, whereby we will be taking it a little easy at sea, but will not have the opportunity to go ashore in most of the ports. Second option was to put in all efforts to bring maintenance up to date in three months or so by working more in these months, whereafter port stays will be freer and at-sea we will only need to do routine work.

Everybody opted for the latter. Luckily, there was a tremendous amount of spares left by the previous staff. They had ordered and received spares to show their office that they planned to carry out a lot of maintenance, but actually did not do so.

I did not need to requisition any spares, as they were already on board and much, much more. Over the years, I found that taking over ships from Norwegians was a boon, as stores and spares were aplenty. The ship’s superintendents sitting in Oslo were very liberal with regard to supply of stores and spares of top quality.

In fact, this abundance of stores and spares caused a reversed opinion of us. We did not need to nor did we requisition any spares or stores during the full year that I was on board. The vessel’s superintendent told me, after 6 months, that we had not spent any of the money allocated in our budget, except for certain consumables like lubricating oil and gases, so please put up some requisitions so that he can look busy in the office. Also, if we do not spend the money allocated to each category, the next year’s budget allocation will be reduced considerably by the Owners. A beautiful Catch 22 situation.

I used to be put into a rather awkward situation, as a visiting Superintendent would spend most of his time with me and ask me the questions that the Chief Engineer should have been answering. They were a little wary of approaching the Chief Engineer, so they spent as little time with him as possible. When I told them that he is a changed man now, they continued to remain wary.

Within three months, we completed all the work and were well ahead of our maintenance schedule. I started giving them off in port to go ashore in batches, so as not to compromise the safety of the vessel at any time. Except for the watch keepers, I could then give off to the day workers during week ends. Quality of work improved. The Engine Room was spick and span. Even copper pipes were polished, which was a rarity. Bilges, tank tops and pipe lines in the bilges were spotless and painted, the pipes with different colours for immediate identification, as per a colour code that I posted in the Engine Room.

Here I was satisfying an oath made to myself in SISCO that I should be able go into the bilges in a spotless boiler suit and come out absolutely clean. In SISCO, it was the other way around and you came out of the bilges filthy.

The level of automation on board this ship, built in 1958, was tremendous compared to SISCO ships built in 1966. The Trianon had automation in the very important aspects of watch keeping. It would require much more to qualify for UMS or ‘Unmanned Machinery Spaces’ certificate, but it was the harbinger of things to come. I studied all the automation on board, although they were pretty basic compared to the sophistication of later years.

The Four 'P's that Govern a Take Over

I had already given some thought on the Chennai Muyarchi to systematic planning to take over a ship as the first crew of one’s Company. It only needed a very clear thought process. What are the priorities that we need to assign ourselves when we take over a vessel from a different Owner? It is also relevant when there is a crew change within the same administration.

########

It actually can be narrowed down to 4 Ps – namely Power, Purification, Propulsion and Pollution.

Power – The generators must be brought to peak efficiency as soon as possible, to avoid problems that can prove calamitous. A black out at the wrong time can be disastrous to the vessel.

Purification – Purifiers must be capable of running at its maximum load, without a break down. Good and efficient purification means good combustion; good combustion means less smoke pollution from Sox and NOx. Efficient Lubricating Oil purification also means a clean crankcase and bearings.

Propulsion – Propulsion covers a host of items of which most are Main Engine related. It has to be taken up in ever expanding stages namely – An Overall View, then a Specific View, followed by an Intense View. If there are problems here, this will take a longer time to resolve, as it requires to be done when the Main Engine is stopped either in port or a forced stoppage at sea, which would involve commercial consequences and, if in bad weather, put the ship in jeopardy.

Pollution – Pollution involves many items to care about. We will assume that the vessel is not involved in a collision that ruptures a tank and, causing an oil spill, pollutes the seas.

Bunkering time on a vessel is a time when the vessel is vulnerable. Improper bunker procedures can cause a spill. Not following a planned sequence in bunkering various tanks can cause a spill. Not taking frequent ullages can overflow a tank and cause a spillage. Closing valves on the line improperly can cause the hose to rupture and cause a spill. A lot of things can go wrong during bunkering. One has to foresee and prevent them from happening and have contingency plans. Not an easy task. By actually carrying out a ‘Risk Assessment” analysis combining it with a step-by-step visualisation of the process, one can mitigate such eventualities.

Another cause of Pollution is from oil in Engine Room Bilges. Bilges must be kept clean, free of any leaks of oil and water. Bilge tank must be kept clean and not allowed to be contaminated with any oil, whereby the Oily Bilge Separator can be used without any trepidation at appropriate times.

########

Chapter 3 – We Load Reefer Cargo for the First Time Since Getting Banned Two Years Ago

We were on round trips called the ‘Willine Run’. 3 ports in Japan, mostly Kobe, Nagoya, Yokohma, then Hong Kong, sometimes Manila, then Singapore - from all of which we would load cargo – then into the Persian Gulf. We would discharge at Dubai, sometimes Abu Dhabi, Dammam, Kuwait, Bahrain and Khorramshahr. We would carry empty containers back.

Another important aspect of this ship was the reefer hold, divided into 6 chambers, each capable of being kept at different temperatures for different cargoes that require refrigeration. One must remember that this was just before the advent of reefer containers into the shipping world. Before arrival Singapore, we were told to keep the Refrigeration Chambers and the Plant ready for possible frozen cargo from Japan. Material for preparing the chambers were supplied in Singapore as per our urgent requisition.

It was a priority cargo of sorts, as the parent company had been banned in Japan and Kuwait from carrying reefer cargo for 2 years. A little over two years ago, one of the parent company vessels had loaded frozen cargo, but the crew did not have the expertise to prepare the chambers and the plant and to know what was needed to be done on the voyage to keep the cargo in good condition. They just ran the plant and recorded the temperatures and nothing else.

When the ship reached Kuwait where the reefer cargo was to be discharged, the top hatch covers on port and starboard sides were opened. All the cargo in the top 2 chambers were frozen solid into a block of ice. Checking on the ‘tween deck chambers and the lower hold chambers by means of the passageway between port and starboard chambers, none of the insulated doors for access to the fan rooms could be opened as they were frozen shut. On shutting off the plant, a few days had to pass for the ice to melt and the mass of soggy cargo had to be thrown out and disposed of. Hence a ban was instituted and all the vessels of the parent company were blacklisted. The cargo was shrimp. Nearly a thousand tons was lost, worth a few million $s.

We had surmised the cause to be fresh air was allowed into the chambers carrying frozen cargo. Fresh air contains humidity and this iced up the cargo. They had been defrosting the coils but had allowed the humidity to build up which, eventually, made the cargo into one block of ice.

We prevented any ingress of air from the ventilators.

Amongst valuable cargoes, refrigerated cargoes earn one of the higher freight rates, all over the world. Carrying reefer cargo successfully is a matter of pride for a shipping company and enhances its reputation in trading circles. It also requires expertise.

Factually, I found that the expertise required was uncomplicated, simple but required constant attention and inspection. All this I learned from my Chief Engineer who had served on Reefer ships. Once the information that we were likely to load this valuable cargo was received, the four of us – Captain, Chief Officer, Chief Engineer, 2nd Engineer (myself) – met and discussed what we would do. Apart from the Chief Engineer, none of us had any experience in carrying Reefer Cargo, in bulk or containerised form.

The Chief Engineer opted to take charge and rubbed his hands in glee. He told me “Second Saab, see, you can’t stop me from working. Work comes to me.” We laughed together. My only stipulation was that he teach me every bit along the way, as we prepared for this cargo that would re-establish the reputation of Wilh Wilhelmsen.

The Chief Engineer was in his element and I was beside him, keeping his exasperation and his temper in check. He had, by then, grown very fond of me and, hence, would listen to what I had to say. Some of the work that we did is listed below.

The chambers’ insulation was checked thoroughly. Insulation material behind the galvanised sheets were found to be in good condition, but quite a few of the galvanised sheets needed re-riveting.

Wooden gratings were repaired or replaced.

All chambers were washed, cleaned and dried out.

The cooling plant was checked thoroughly. All cooling fans’ motors were checked. About 4 of them showed low insulation and were overhauled. The 4 Reefer compressors were checked for efficiency, one had to be overhauled, others found to be in good order. Oil filters on the discharge of the compressor (that prevents compressor crankcase oil from getting carried over into the system) were cleaned out. Silica gel dryers were renewed. Return filters were cleaned. The system had some air, which was removed. Sintered filters on Expansion Valves were replaced. Reefer spares were checked and organised. Leak checks were carried out. All staff were trained in checking the plant and spotting abnormalities.

I do not remember if the system used Freon 12 or Freon 22, both of which are now considered ozone depleting and is banned by the Tokyo(?) protocol.

The fan room or the cooling chamber had coils that carried the gas. When in operation, the outside of these coils should have a thin film of frost. If there is a lot of moisture in the air, the coils get badly iced up, preventing heat transfer from taking place. Room temperatures then start to rise, leading to cargo damage.

In smaller rooms, like the vessel’s meat room or fish room, there are electric heaters placed close to the coils which come on automatically during the defrost cycle, which time and duration can be adjusted on a clock device.

The reefer cargo chambers did not have any electric heaters. Instead it had a sprinkler system where water from the General Service Pumps can be used to spray down on the coils and remove the ice. The advantage was that sea water for this spray method could be kept at around 3 to 4 bar, due to which the defrosting operation lasted a very short period. The disadvantage was that sea water corrodes. So we rerouted the system and fabricated pipelines in such a way that fresh water also can be used for defrosting, but separately. During the loaded voyage we found that using fresh water at shorter intervals for defrosting was more efficient.

Clogged drains in the chambers, leading to the Engine Room bilges, were cleared. A solution of brine was poured into the drain, so that the trap was filled with brine to prevent gases and odours from coming up. It would allow water from the chambers to drain, but the brine would need replacing on a regular basis. The drains that led to the Engine Room bilges were festooned with ribbons, which would flutter if the brine seal was lost, because air would course through the pipes when the fans were running and fresh air would enter when the fans had cut out, on the basis of a thermostatic sequence.

Brine Trap shown on the right – courtesy Google

48 hours prior arrival Yokohama, the chambers had been cooled down and maintained below -20oC. At Yokohama there was a survey done prior loading to ascertain there were no faults in the system. The cargo of shrimps in cartons that were already frozen were loaded. Random cartons were checked with a ‘poke-in’ thermometer to check and record the temperature at which the cargo was loaded.

Because of the design of the hold, much as in the dry cargo holds, loading had to begin with the Lower Hold, then close the Lower Hold pontoon. Next the Lower ‘Tween Deck is loaded followed by the Upper ‘Tween Deck, after which the top Hatch Cover(s) are closed and cleats tightened. In order to prevent any ingress of fresh, humid air, the deck ventilators and air pipes are closed and sealed off, if necessary, with a canvas shroud tightly tied around the ventilator.

The cartons of shrimps cannot be loaded one on top of the other. They have to be loaded like laying bricks and have a small gap between horizontal cartons, so that the air flow is in a zig-zag manner. This way all cartons get the benefit of the cold air. If I remember right, the air flow is from the top of the cargo to the fans, which then discharges this air past the cooling coils and the space below the grating on which the cargo is stacked. Then through a zig-zag path between the cartons, the air once again reaches the top.

===== Blog 47 continues =====

Comments