BLOG 35 - Marine Musings 7 - Chennai Muyarchi And My First B&W Engine

- ranganathanblog

- May 4, 2022

- 13 min read

Marine Musings 7 – Chennai Muyarchi

From 7th June 1974 to 18th Oct 1974

CHENNAI MUYARCHI - IMO 7235848

Vessel type: Bulk Carrier

Gross tonnage: 30,325 tons

Summer DWT: 53,439 tons

Build year: 1973

Gross tonnage 30325 tons

Deadweight 53439 tons

Length 206 m

Breadth 29 m

Year of build 1973

Builder NAVANTIA CARENAS MADRID - MADRID, SPAIN

Chapter 1 – I join the Muyarchi at El Ferrol in Spain – A new type of Engine (B&W) – I am still a 3rd Engineer

For the first time, I was given an airplane ticket by the Company and flew at Company expense from India to Spain. Chennai to Mumbai was a domestic flight on Indian Airlines. Then an Air India flight from Mumbai’s Santa Cruz airport took us to Madrid, Spain. There were 35 or so of us who had come together at Mumbai and were flying on Air India. Most of the senior staff were already on board.

I was, as 3rd Engineer, the senior most of the ship’s crew on this flight and was deputed by the Company to take charge and maintain discipline. What discipline? I was meeting them all for the first time. As soon as the flight was in the air, because the drinks were free, quite a number of the crew were flying high. I only told them all that they should behave in a decorous manner with the stewardesses, no shouting, no obscenity. The stewardesses, thankful that I could control them, upgraded me to Business Class and looked after me very well. That was the first time I had a few ‘cocktails’ as recommended to me by the stewardesses. The food was excellent, the canapes even more so.

We landed at Madrid and had to wait quite a few hours in Madrid. The Agent at El Ferrol was supposed to make the Madrid-to-El Ferrol arrangements but he had slipped up. We were stuck in Madrid airport, without food or confirmed flights. Air India said that their responsibility ceased once the passenger has disembarked and rightly so. Our Ship's Crew’s Union Rules are that food and accommodation is to be provided to stranded crew by the Company. If not, it could become a big issue later on, leading to heavy compensation amounts.

Here I was, as leader of the group and, in the crew’s eyes, the Company’s representative. Once again, my resourcefulness in man management, away from my comfort zone of the Engine Room, was being tested. The crew were hungry. First, they had to be fed. The Officers and some of the crew pooled in all the dollars we had and we all had something to eat at the airport.

I had no telephone number for the El Ferrol Agent but had his Office Address. I persuaded a reluctant Spanish airport official to find the number and call the Agent. It seems that the Agent’s assistant, who was supposed to make the arrangements, had fallen ill without making arrangements. The Agent’s Madrid office came out to help, procured us our flights in 2 small planes and we landed at El Ferrol. We stayed in a very quaint hotel for 2 days before being taken to the ship. Vegetarian food was hard to come by, hence I had to subsist on eggs, bread, jam, butter and milk.

Chapter 2 – The Ship

At the first sighting of the ship, it looked strange. Then it struck me – there were no cranes on deck. The absence of cranes meant that the vessel can only berth at piers having means of discharging, like grabs for the heavier cargoes and suction arms for grain. If I recollect correctly, the second difference was the side rolling hatches, operated by hydraulic motors. The other ‘Chennai’ ships had ‘concertina’ type Macgregor hatch covers that would fold one on to another, in a fore-and-aft direction, sometimes troublesome. The ‘Muyarchi’ hatch covers had hydraulic jacks that lifted the covers till they were in line with the rails and would move in the port and starboard directions, using chains. (Representation below)

The accommodation was not as luxurious as expected of a ship built in Europe for Europeans, only marginally better than the other German built ‘Chennai’ ships.

The Engine Room was different in every way. The Main Engine was a Burmeister & Wain (B&W) engine (of Danish manufacture?), with exhaust valves on top, operated by push rods, rocker arms and springs.

ABOVE IS A TYPICAL AND MORE MODERN 12 CYLINDERED B&W ENGINE WITH HYDRAULICALLY OPERATED EXHAUST VALVES. AN AVERAGE SIZED HUMAN IS DEPICTED IN THE BOTTOM RIGHT HAND CORNER TO REPRESENT SIZE OF THE ENGINE.

REPLACE THE HYDRAULICALLY OPERATED EXHAUST VALVES WITH ROCKER ARM & PUSH ROD OPERATED EXHAUST VALVES, REDUCE THE NUMBER OF CYLINDERS TO 6 AND YOU NEARLY HAVE A CONFIGURATION OF THE

‘CHENNAI MUYARCHI’ ENGINE.

(2 Stroke Marine Diesel Engine MAN B&W: Operating Principle

I request all to watch this excellent video. Please copy-paste this link on to your browser. I include my die hard engineering colleagues also.

This video is almost similar to the engine on the Chennai Muyarchi and what we do in the Engine Room. Acknowledging, with thanks, ‘Supreme Engineer’ on You Tube, for this excellent video.

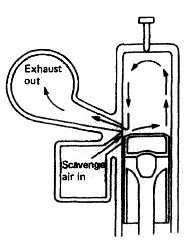

This engine, with an exhaust valve on top, was meant to facilitate ‘Uniflow Scavenging’, unlike the ‘Loop Scavenged’ MAN engines that I had been working on till now. I was coming across this for the first time, although I had studied them in text textbooks for my exams.

Uniflow Scavenging

The right side is applicable to the ‘Chennai Muyarchi’.

Loop scavenging as in the German built ‘Chennai’ ships with MAN Engines

The difference between ‘Uniflow’ and ‘Loop Scavenging’ was immediately obvious during engine operation. The ports were clean and did not choke up with carbon, which resulted in a cleaner scavenge space, better air flow, good combustion, lower exhaust temperatures, better specific fuel consumption and many more benefits. Lesser man hours were spent in cleaning ports and scavenge spaces, so man hours could be diverted to other areas.

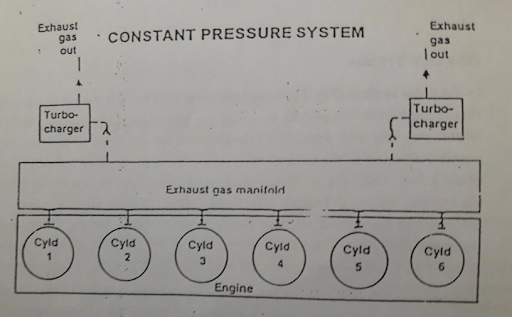

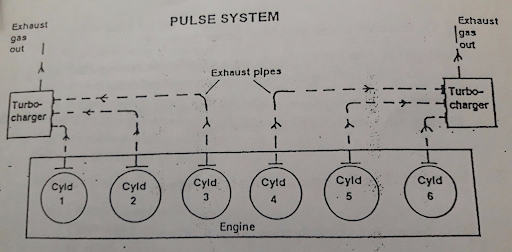

Another glaring difference, of which I had, till then, only book knowledge, was the method of exhaust flow, ‘Constant Pressure’ on the ‘Muyarchi’ vs ‘Pulse System’ on the other ships.

This made a difference to the response times of the speeding up of the turbochargers.

Constant Pressure system of turbocharging meant a slower response at lower engine speeds (or rpm), which meant that not enough air is supplied to the engine during the ‘pick up’ of rpm, necessitating one or two motor driven auxiliary blowers to augment air supply. But at higher rpm, it was an advantage. The auxiliary blowers would cut off automatically and the turbochargers would build speed slowly but steadily and would remain steady during full speed operation.

The Pulse System of turbocharging would give sufficient air to the engine at lower rpm, but was very susceptible to unbalanced Horse Power difference generated by each cylinder, which made the turbocharger speeds change constantly.

One other major difference were the turbochargers. The ‘Chennai’ MAN ships had MAN turbochargers with sleeve bearings and an outside source of lubrication under pressure. They were the only ships I came across that had sleeve bearings fitted to the turbochargers. They also required a header tank of nearly 2000 litre capacity. In the event of a failure of the main Lubricating Oil Pump, the Header Tank oil will drain down slowly, over a period of 10 minutes to keep the bearings lubricated, as it will take that long for the turbocharger to stop.

The ‘Muyarchi’ had Brown Boveri (BBC) turbochargers, which had 2 attached Lubricating Pumps, one on the air side and one on the exhaust side, with their own independent lubricating oil sumps. Many of the other turbocharger manufacturers, like Mitsubishi, had similar arrangements.

What is the difference and how does it affect the ship? The MAN turbochargers were more robust and could take slight deviations in clearances without failing. The BBC turbochargers needed precise assembly and fine tolerances, after which they were a dream.

The BBC turbochargers had roller bearings that needed to be changed and renewed after a certain number of running hours. In the initial days, ship’s staff had sufficient expertise to undertake this slightly complicated disassembly, overhaul, ensuring correct tolerances, final assembly and trial.

As the years went by, accidents due to wrong assembly or improper adjustment of tolerances, cost many a Company dear, as the wrongly assembled BBC Turbocharger would get hot, the and bearings would burn out in 10 to 15 minutes of starting the engine. The vessel would be left without engines at a very critical juncture. These breakdowns and subsequent accidents led to Companies opting to call in manufacturer’s service personnel to overhaul the BBC turbochargers. Nowadays, it is a given that service engineers are called to overhaul the turbochargers.

The reader may wonder why I am devoting many pages to emphasise the type of engine. There is a purpose. Within a decade of my being at sea, Loop Scavenged engines with Pulse System of turbocharging almost disappeared from the scene, to be replaced by Engines with Hydraulically operated Exhaust valves with Uniflow Scavenging and Constant Pressure Exhausting for Turbochargers. I think it was in the 1980s that MAN acquired B&W and used the B&W technology of the Uniflow design to further their market clout.

The use of push rods and rocker arms were phased out in the 1980s and replaced with hydraulically operated exhaust valves. In the 1970s, the only ship in SISCO’s inventory with B&W VT 2BF Engines was the ‘Chennai Muyarchi’. But after leaving SISCO, I worked on many old vessels with similar VT2BF engines and learnt a lot about them. After that I graduated to more modern engines manufactured by B&W, MAN B&W, Sulzer, Pielstick V Type Engines and others. Many of the MAN B&W engines were licensees like Hyundai, Hitachi.

But the satisfying sounds of a B&W VT2BF engine in operation are sounds one never forgets. It is a symphony, orchestrated by a master conductor. From the quiet ‘whoosh’ sounds made when starting air is introduced, to the ‘clickety clack’ of the push rods and rocker arms, to the ‘humph’ sound made by the exhaust valve opening, to the ‘hum’ of the chain drive, to the small ‘tup’ sound made by the two injectors as they inject fuel – it was all music to my ears. As the engine speeds up, except for the starting air that is automatically shut off, all other sounds come together in military unison to produce a symphony.

The firing order for this engine 1-5-3-6-2-4, so there is a 60 degree offset.

Just imagine all the sounds described above going through a cycle offset by 60 degrees. An engineering symphony.

The more modern B&W engine, like no other engine for that matter, filled my ears with such music.

“O Listen for the vale profound

Is overflowing with the sound”.

In contrast, the MAN loop scavenged engine, with camshaft that was driven by a gear train, was much noisier. Of course, in both type of engines the turbochargers’ decibel levels used to be high. With more and more exposure to this noise, even with ear protectors at a later stage, my hearing deteriorated later in life, the damage having been done in the first six years, when ear protective equipment was not provided for us. Later, in my sixties, I found that I had lost about 60% of my hearing.

Sometimes – the reader may say ‘quite a few times’ – I digress away from the narrative at hand, which is now about the ‘Chennai Muyarchi’. My excuse is that one sequence of thought opens the floodgates to many more of its kind, and those span across 4 decades. If I were to give it in parts, the significance of it would be lost on the reader, as he may not piece together what I had written in an earlier segment.

Getting back to the ‘Chennai Muyarchi’, we took over from the Spanish. My convoluted mind was thinking ‘Why would a ship owner sell a 2 year old bulk carrier when the freight rates were good and the market was good?’. A couple of months later, we thought we had stumbled on the truth, which is for later, after we sail out of Spain.

Being a Spanish ship with Spanish staff, everything was in Spanish – the manuals, the drawings, the labels – confusing the hell out of everybody for a few days, till we learned to cope. We were able to get a very few of the important manuals in English. We had to make do with a few Spanish to English dictionaries.

I do not have much of a recollection of exactly where we sailed to or any of the ports that I visited during my stay on the ‘Muyarchi’.

But I have a vivid recollection of a burnt exhaust valve at sea, which forced us to stop and change the exhaust valve. I was tasked with starting this job, with the 2nd Engineer relieving me at 4PM, as the initial estimate of doing the job was 8 hours. None of the Engineers had any knowledge of the intricacies of the B&W engine, so we had jointly come to the conclusion that the rocker arm pedestal needed to be removed before we removed the exhaust valve. The way we visualized it the job would take a minimum of 8 hours. Everybody went up leaving me with 2 motormen and a Fireman. Like I said all the Engineers were pure bred SISCO personnel and had worked on only MAN engines. Even the Motormen were from the same mould. But the Fireman was from the Seaman’s Union (NUSI), who supplied the crew to all Indian registered and to quite a few foreign vessels, especially UK registered.

We got the tools together and started tackling the removal of the rocker arm pedestal. That is when the Fireman said “Theen saab, kya kaam karna hai abhi?” (“Third Engineer, what is the job that needs to be done?”). I told him that we have to change the exhaust valve because it is burnt, He said “Iske liye pedestal nikalne ka zaroorat nahin hai” (There is no need to remove the pedestal for this’).

Then he showed us how. A wire rope slung around the push rod end of the rocker arm, a chain block suspended on the crane was enough to slowly lift the rocker arm to a height just enough for the push rod to be taken out at a slant. Then the rocker arm can be let down so that it is free off the exhaust valve, having rotated 90 degrees on its fulcrum. Remove the exhaust trunking bolts and the 4 securing nuts of the exhaust valve and the exhaust valve is free to be lifted out with the crane.

We cleaned all parts, changed all the O rings, changed the gaskets on the right angled Cooling Water elbows, applied anti-seize compounds and lowered the exhaust valve. Within a space of 2 hours, the entire job was complete, with the Fireman leading the work and showing us exactly how. He was quite a young lad, only 21 or so, but had worked on 2 ships with B&W engines. I sent him a bottle of VAT 69.

We were on the move even before the 2nd Engineer could come down. He and the Chief Engineer wanted to know the details of how I managed to finish in 2 hours for what had been estimated as an 8 hour job. I gave credit where it was due, to the Fireman, and also detailed how the job was done.

We had completed the job in 2 hours the first time around. In later years, on other ships belonging to Wilh Willhelmsen of Oslo, we had reached a peak efficiency of doing the same job in 22 minutes, when I was in charge of the group. That was job satisfaction, with my working on a Scindia ship‘s fuel pumps (as related in my ‘Perumai’ Musings) being the topper.

The Main Engine was, later, found to have a problem, where the engine would sometimes miss a couple of astern starts, but would eventually come through. This used to happen once in a while. This is where I first started practically going through pneumatic systems for the Main Engine. As long as I was there, this problem existed (4 odd months) and was not resolved. A lurking feeling that this was one of the causes why the Spanish sold us a 2 year old ship came to my mind.

My batchmate Phiroze Patel, who sailed on this ship about 2 years later, told me that the problem was resolved during his tenure. During his checks on the pneumatic system and its valves, he found one of the main pneumatic valves for reversing had a plastic plug in place, which should not have been there, as that aperture was venting the accumulated air after the reversing sequence was completed. All valves, when they come new from the manufacturers, have plastic plugs fitted in all apertures to ensure that no dirt or water enters the valve before being fitted into the system. All these plugs are supposed to be removed, once the system is assembled.

Needless to say, the problem of missed astern starts vanished. On such a simple neglect hangs the fate of many lives.

I remember spending quite a bit of my free time in writing up notes on the B&W Engine, as the knowledge would come in handy for my Chief Engineer’s exams.

I think we went through the Panama Canal on that voyage, but I have no recollection of it. I will write up about the Panama Canal when I narrate my tenure aboard a ship that crossed the Canal pretty often, as it deserves mention, much as the crossing of the Kiel Canal, Suez Canal and the Equator are all milestones in a seafarer’s life.

About a week before the ship reached Japan, a message was received on board to sign me off in Japan, in order for me to be promoted as 2nd Engineer on the ‘Chennai Sadhanai’. My CDC records show that I signed off the ‘Chennai Muyarchi’ at Mizushima, Japan, on 18th Oct 1974. I had been on board for only 4 months and 11 days. At that point of time, I had about 7 months of sea time left to complete, in order to be eligible for writing my Chief’s exam.

Chapter 3 – What I had learnt on the ‘Chennai Muyarchi’ – What were the Takeaways

Learning about a new and completely different type of engine was a challenge and gave me a purpose of wanting to discover and know more about other engines, other ships, other layouts, other systems.

I surmised that, as long as I was working on the 5 sister ships that SISCO, apart from the Chennai Muyarchi, I was like a frog in a well which thought that the well was the world. Due to working on a second type of engine, my professional interest was piqued and I started wondering how to acquiesce that pique.

One of the important takeaways was ‘Do not take your crew lightly’. At least listen to their advice, it will be worth it. The last in the pecking order in the Engine Room was the Fireman – in Foreign companies he is known as a Wiper – but he came up with the correct method of doing a job. It stood me in good stead over the years. Sometimes, consulting a crew member makes him a more willing worker.

Lying low and not flouting your knowledge will pay dividends. If you have the skills or the knowledge, it will somehow or the other get to be known by others, without your trumpeting it. Your reputation will spread without your knowing it.

Taking over a ship from a different owner and being the first staff from SISCO to sail on it, required a different approach than just joining a ship where all the others are already familiar with systems. Here it needed a very systematic plan. It made me ponder and led to many self made check lists at later times. Little did I know that 'check lists' were to become the main stay of a seafarer's life, not his knowledge.

Rangan

Comments