Blog 128 - Slavery and the Coloniser - Part 1

- ranganathanblog

- Mar 12, 2024

- 13 min read

Slavery and the Coloniser - Part I

England and the ‘Doctrine of Discovery’

Spain entered the Slave Trade in 1441, using two Portuguese citizens to captain their ships.

Portugal entered the Slave Trade in 1444.

Both nations hunted down the occupants of villages in the North West Coast of Africa,, chained them and transported them across the Atlantic to various North and South American states, sold them like cattle to land owners who were in desperate need of cheap labour to work their fields.

A very lucrative business line was, then, set up which benefited the only two players in the trade, the Portuguese and the Spanish, the two dominant naval powers of that time. But their rivalry took on proportions that were less friendly and more violent, with each country raiding and attacking the other.

Both being Catholic countries, the Pope, in 1493, stepped in and brought a semblance of peace between the two with a ‘Bull’ to carve out the entire world into two spheres of influence, in what came to be known as the ‘Doctrine of Discovery’.

All went well for a while, with both countries raking in the treasures and wealth of far off nations as well as the riches of the Slave Trade.

But their naval superiority was challenged by Britain towards the final years of the 1400s and by the Dutch in the 1500s.

Both, the English and the Dutch were, at that time, slowly coming under the thrall of the Protestant Reformation started by Martin Luther, who had nailed his 95 revolutionary opinions to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg on 31st Oct 1517.

Some nations, including the English, were not at all happy over the favourable treatment meted out to the Spanish and the Portuguese by the Pope in Rome and which had excluded them from the harvests of the ‘Doctrine of Discovery’.

Without overtly defying the Pope’s ‘Doctrine of Discovery’ the English navy slowly started asserting themselves and, by the mid 1500s, had started gaining naval superiority.

Which led them to become one of the key players in the trans - Atlantic Slave Trade from 1562. Skirmishes with the Portuguese and Spanish fleet were common.

The Decimation of the Spanish Armada

Irked by the ascendency of the English in what they considered to be their domain, the Spanish Armada set sail - in 1588 - to, once and for all, deny and destroy the English by landing troops on English soil.

The Spanish invasion also had religious overtones, as England’s Elizabeth I, on her ascending the throne in 1558, forced Parliament to pass the ‘Act of Supremacy’ and made it into law, which Act renounced the supremacy and powers of the Pope and brought into force allegiance to the Throne and the Church of England. In effect, the supremacy of the Pope in national affairs was diluted significantly.

With the rise of English naval supremacy and the subsequent raids on Spanish and Portuguese ships and bastions + the strained papal relationships, it was inevitable that Spain would, with the covert backing of Rome, prepare for war with England. But their overconfidence on the basis of their numerical superiority in ships and troops, proved to be their undoing.

Nobody took into account the fact that the range of the English ships’ cannon was further / longer than the Spanish ships. Added to it was the subterfuge and the guerrilla tactics used by the English to instil confusion in the ranks of the Spanish, be it naval or land troops.

The Armada was huge, with hundreds of ships. They dropped anchor in Calais, France, to await a huge land - trained army contingent for crossing the Channel for the final assault on the English.

However, the delays in mustering the troops and loading them on board gave the English the opportunity to plan a surprise counter attack. The counter attack came in the form of fire ships.

The English naval fleet’s second-in-command was Sir Francis Drake, that wily pirate who had numerous naval exploits under his belt. He sent in 8 ships loaded with inflammables into the midst of the anchored Spanish fleet and set his own ships on fire. A few Spanish ships were lost due to the fire engulfing them. But the confusion caused by the fires made most ships of the Armada cut their anchor cables and scatter into the English Channel.

Individually, the larger, more sluggish, galleons of the Spanish were not fast enough to defeat the English navy’s faster, smaller, more maneuverable ships. The Spanish were constrained to a single plan - sail within reach of the English ships and, using grappling hooks, board them and overcome them by sheer weight of numbers.

But the English ships proved more agile and used their longer range cannon to good effect to destroy the Spanish ships one by one, now that they were scattered in the confusion caused by the fire ships.

The Dutch also lent a hand in subduing the Spanish.

Thus, an Armada was decimated, never to rise again.

England and the Slave Trade

Now that they had entered the very lucrative 3 way Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade in 1562 and, combined with their naval superiority, they did not relinquish control over the Slave Trade officially till 1833.

In August 1833, Parliament passed An Act for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Colonies, converting enslaved people into apprentice labourers and taking steps to protect their work and well being.

But, in the intervening centuries, as per Royal Museums Greenwich, the Key facts that they put out about the transatlantic slave trade

Between 1662 and 1807 British and British colonial ships purchased an estimated 3,415,500 Africans. Of this number, 2,964,800 survived the 'middle passage' and were sold into slavery in the Americas.

The transatlantic slave trade was the largest forced migration in human history and completely changed Africa, the Americas and Europe.

Only Portugal/Brazil transported more Africans across the Atlantic than Britain.

Until the 1730s, London dominated the British trade in enslaved people. It continued to send ships to West Africa until the end of the trade in 1807.

Because of the sheer size of London and the scale of the port’s activities, it is often forgotten that the capital was a major slaving centre.

Between 1699 and 1807, British and British colonial ports mounted 12,103 slaving voyages - with 3,351 setting out from London.

Although, in effect, the Slavery Abolition Act was passed in 1833, all it did was make the trade more clandestine, more black marketish. It continued in one guise or another till well into the 20th century.

(I will desist from being more eloquent about the Slave Trade, as I have already given the subject a lot of bytes in a previous article “The Three Nadirs”).

Now we come to India.

“THE INDIAN SLAVERY ACT, 1843 ACT No. V. Of 1843 [7th April, 1843]. Passed by the Right Hon'ble the President of the Council of India in Council, On the 7th of April, 1843, with the assent of the Right Hon'ble the Governor General of India.”

But something more draconian had already been set in motion in India, by the British colonisers.

==================================================

How the East India Company spread its Wings

Before we get to the draconian measures taken, let us go back to the spread of British colonialism, how it took root and the drastic humanitarian consequences.

‘Brittanica’ says “The East India Company was an English company formed for the exploitation of trade with East and Southeast Asia and India. Incorporated by royal charter on December 31, 1600, it was started as a monopolistic trading body so that England could participate in the East Indian spice trade. It also traded cotton, silk, indigo, saltpeter, and tea and transported slaves. It became involved in politics and acted as an agent of British imperialism in India from the early 18th century to the mid-19th century. From the late 18th century it gradually lost both commercial and political control. In 1873 it ceased to exist as a legal entity.”

John Mildenhall was the first British explorer of these times to make an impact on the Indian polity. He was a self styled ambassador of the British East India Company in India. Mildenhall reached Lahore in 1603 and, later, presented himself at the Mughal ruler Akbar’s court.

“Red Dragon” was the first British East India Company ship that came to India. The East India Company used her for at least five voyages to the East Indies. In October 1619, a Dutch fleet attacked Red Dragon and sank her. “Hector” was another British ship by which traders of East India Company came in India in 1600 CE.

As was the climate of the times, Cumberland was a gambler, privateer, who had the ear of the monarch, Elizabeth I, James I and, later, Charles I. He was one of the founder members of the British East India Company and a favourite of Elizabeth I.

The first foothold had been created in the colonisation of India.

Between the years 1603 and 1612, East India Company sent 21 ships to India, investing a total of 408,00 British Pounds,, averaging about 19,000 Pounds per ship. Between the years 1613 and 1616, they sent a total of 29 ships, total investment 273,000 British Pounds, average 9,400 British Pounds.

In just 13 years, their investments were halved, with the loss of one ship. Their voyages between 1613 and 1616 netted them between 7 to 10 times their investment.

Wikipedia says:

“The company's first Indian factory was established in 1611 at Masulipatnam on the Andhra Coast of the Bay of Bengal, and its second in 1615 at Surat. The high profits reported by the company after landing in India initially prompted James I to grant subsidiary licences to other trading companies in England.”

They wanted more of the pie and requested James I to parley with the then Mughal ruler Jehangir. Sir Thomas Roe met Jahangir and this is what transpired.

“In 1615, James I instructed Sir Thomas Roe to visit the Mughal Emperor Nur-ud-din Salim Jahangir (r. 1605–1627) to arrange for a commercial treaty that would give the company exclusive rights to reside and establish factories in Surat and other areas. In return, the company offered to provide the Emperor with goods and rarities from the European market. This mission was highly successful, and Jahangir sent the following letter to James through Sir Thomas Roe.

“Upon which assurance of your royal love I have given my general command to all the kingdoms and ports of my dominions to receive all the merchants of the English nation as the subjects of my friend; that in what place soever they choose to live, they may have free liberty without any restraint; and at what port soever they shall arrive, that neither Portugal nor any other shall dare to molest their quiet; and in what city soever they shall have residence, I have commanded all my governors and captains to give them freedom answerable to their own desires; to sell, buy, and to transport into their country at their pleasure. For confirmation of our love and friendship, I desire your Majesty to command your merchants to bring in their ships of all sorts of rarities and rich goods fit for my palace; and that you be pleased to send me your royal letters by every opportunity, that I may rejoice in your health and prosperous affairs; that our friendship may be interchanged and eternal.

— Nuruddin Salim Jahangir, Letter to James I.”

India was sold to the British by Jahangir for a few European trinkets.

The emperor Jahangir investing a courtier with a robe of honour, watched by Sir Thomas Roe, English ambassador to the court of Jahangir at Agra from 1615 to 1618, and others

Once the foothold was gained, consolidation started. English troops, with arms, guns and cannon totally different and superior to those used by the local police or the ruler’s troops, were brought in in large numbers to, ostensibly, ‘protect’ their outposts and investments but, in reality, to expand their sphere of influence.

In doing so, they met with resistance from the French, who were also, simultaneously, trying to expand their sphere of influence. Conflict with the French was inevitable.

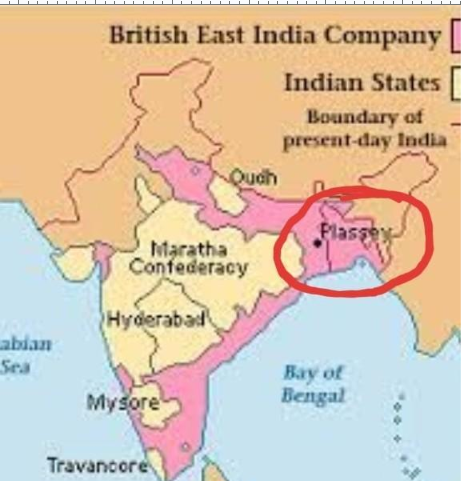

In the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the English under the command of Robert Clive defeated the French in the Northern Hemisphere.

The Southern Hemisphere had a similar battle, the Battle of Wandiwash, for supremacy of the South, the English winning decisively in both cases.

Location of Wandiwash in Tamil Nadu

Incidentally, Wandiwash - British pronunciation - now known as Vandavasi, is my birth place.

One of the titbits of history is the fact that Bombay was given as dowry to Prince Charles. “As a marriage treaty the King was given a huge dowry by the Portuguese. As a part of that dowry, Portugal handed over the city of Bombay and Tangiers to Charles II on 3rd July 1661.”

We had been reduced to this kind of plight where entire cities of ours were bandied about by monarchs far removed from us.

The English have now ensconced themselves firmly in India.

==================================================

Governors, Governor Generals and Famines

From now, the focus of the article will be on famines.

Modern definition of famine:

“Action Against Hunger” defines it as

“A famine is defined as the most severe kind of hunger crisis. It is very rare, but when it does occur, it means that there is an extreme shortage of food and several children and adults within a certain area are dying of hunger on a daily basis.

Some deadly emergencies happen suddenly, like earthquakes, floods, and other natural disasters. This is not the case with famine. A famine happens slowly, caused by long-term conflict, climate shocks, extreme poverty, and other drivers. Famines are never inevitable – they are always predictable, preventable, and man-made.”

Famine is a technical term – it is only officially declared when a series of specific food insecurity, mortality, and malnutrition criteria are met.

20% - 1 in 5 households face extreme food shortages

30% - More than 3 in 10 people are malnourished

2 in every 10,000 people die every day of hunger

4 in every 10,000 children under five die every day of hunger. To declare a famine, the world turns to the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) system, a framework involving governments, UN agencies, organizations like Action Against Hunger, civil society, and other relevant partners. Together, using the IPC’s scientific standards and analytical approach, partners classify the severity and magnitude of food crises in a country.

The IPC has five phases for hunger crises, ranging from Phase 1 (Minimal/None) to Phase 5 (Catastrophic/Famine), and each has its own set of technical criteria.

Phase 1 : Minimal : Where 4 in 5 households are able to meet essential needs without engaging in atypical strategies, such as trying to boost income or indulge in abnormal methods to procure food.

Phase 2 : Stressed : Even with humanitarian assistance, one in five house holds have just minimal essential foods. but procuring other non-food essentials is difficult.

Phase 3 : Crisis : Even with humanitarian assistance, one in 5 households are able to meet their essential food needs only through selling off some assets, like cultivable land or properties or livestock.

Phase 4 : Emergency : Even with any humanitarian assistance, one in 5 households have extreme malnutrition and food shortage, leading to even deaths and loss of assets - cultivable land, property, livestock - through sale to stave off hunger.

Phase 5 : Catastrophic Famine : Even with any humanitarian assistance, one in 5 households face extreme malnutrition and heavy mortality and are unable to rise up above this state.

The rationality between all these 5 phases is the emphasis on 20% of households., on which all phases are evaluated.

Another organisation measures ‘famine’ in a different way:

“A "major famine" is defined according to a magnitude scale, which is an end-to-end assessment based on total excess death. According to it:

(a) a minor famine is accompanied by less than 999 excess deaths);

(b) a moderate famine by between 1,000 and 9,999 excess deaths;

(c) a major famine by between 10,000 and 99,999 excess deaths;

(d) a great famine by between 100,000 and 999,999 excess deaths; and

(e) a catastrophic famine by more than 1 million excess deaths”.

The British, of those times (18th century) did not seem to have much of an idea of measures to contain a famine, as evinced by the way they stumbled through a severe famine during the period 1845 to 1852, with Ireland facing the brunt of the famine in the form of ‘Potato Blight’. As many as 1,000,000 were reputed to have lost their lives, while a huge majority migrated to distant lands. Irish nationalism was born.

In India, the first recorded administrative plans for famine relief goes back to more than 2000 years, with Chanakya formulating relief measures in case of a famine. This was after studying historical and geographical events of failure of monsoons, floods, drought.

The Chola period, of which I made a 5 part study, was a prime example of ‘Disaster Management Plans’ set up well in advance of actual events. Examples were the huge urns - shaped like the modern day cooling towers of power plants but much smaller - that were kept filled with fresh grain each year when the harvest was bountiful. This extended across the kingdom to even the smallest of villages. Drought or famine or floods in one kingdom triggered a positive response from a neighbouring kingdom. Hence mortality rates were pretty much non existent.

==================================================

If one takes India, pre British, pre Mughal, there have been a few recorded famines across the country.

The first recorded famine was in the aftermath of the Kalinga war, more due to the scorched earth policy of Asoka’s army. The famine was confined to the Kalinga (now Orissa) area, where the farmers lost their crops and civilians lost their lives.’

“Periya Puranam”, a Tamil epic written in the 12th century - part philosophical, part religious on account of Sekkizhar’s writing about the lives of the 63 ‘Nayanars’ or saints who were devoted to Lord Shiva, part historical, part administrative and part political science for the statecraft of the kings and rulers, mentions a 7th century famine in Thanjavur - the Granary of the South - and measures undertaken to overcome the famine.

The Durga Devi famine in South India, between 1396 to 1407, is mentioned but not in detail, presumably not having any major impact.

The famine of 1639 to 1642 in the Deccan and Gujarat was one of the worst on record till then, proving to be the death knell for about 3 million in Gujarat and about a million in the Deccan.

The Deccan seemed to have suffered from the ravages of famine often enough - in 1665, 1682, 1702 ~ 1704 (which killed nearly 2 million), 1772 and 1884.

On most occasions when a famine was emerging or was rampant, good rulers acted swiftly. Having to deal with, mostly, an agrarian, rural, agriculturist society, they cut or abolished taxes in that area, started public works in the area to bring about employment to the farmers, imported food grains, set up relief kitchens and, in general, provided relief till the worst was over. It was only when the rulers were unfit or were tyrants that one heard of millions dying.

In the Southern part of India, temples were pools of refuge during troublesome times such as famine or floods. Temple wealth was used in abundance to import food grains from far off places which had abundant food supplies and distributed to the starving. It became the pillar of support to the entire community.

The more discerning reader may be wondering where all the disparate issues of the Armada, slavery, coloniser, famine etc are leading to. I expect to link them all together soon in, what I hope will be, an interesting finale.

Rangan

Comments