Blog 111 == ISM Code = Safety Management Systems = Rest Hours = Audits = Non Conformities

- ranganathanblog

- Jan 25, 2023

- 12 min read

(The narrative below is a continuation of Blog 110).

The inculcation of ISO 9000 standards also buttressed SOLAS in many ways.

For example, a shipyard could purchase the steel required to build a ship from almost any source, whether dubious or otherwise. With the implementation of ISO 9000++ standards, they were forced to purchase steel that had been laboratory tested in front of a Classification Surveyor and was up to the standards specified by the Classification Society.

As stated before, the International Safety Management Code, ISM Code, grew out of the articles of ISO 9000.

It grew out of a need for the shipping industry as a whole to improve its standards, improve its quality, increase its level of responsibility, accept its accountability.

It grew out of a need for all ancillary partners to a ship - the workshop, the ship’s chandler, the spare parts supplier, the ship’s Agent, the Classification Society - to maintain a certain level of quality in their support.

It grew out of a need to inculcate a sense of responsibility and accountability on the part of the Ship Owner or Manager.

In the initial phase of the implementation of ISM standards, I was confident that it would reduce the workload on the seafarer serving the ship.

What really happened was that most Companies - whether Owner or Manager - very astutely passed on the burden of responsibility and accountability back on to the seafarer by officially coding actions to be taken by the ship in 2 or 3 volumes of instructions in the form of a Safety Management System.

Every conceivable scenario was visualised and a check list formulated for the ship to fill. Check lists became exhaustive, involving the inclusion of too many parameters. Check lists grew in number, as situations faced by one ship in reality were immediately transformed into a ‘check list’ and added to the Safety Management System manual.

Safety Management - SMS - manuals grew to 3 or 4 volumes- Bridge Procedures and Check Lists - Engine Procedures and Check Lists - Deck Operations and Check Lists - General Procedures and Check Lists - totalling more than a 1000 pages in some cases. A ‘Ship Specific’ Procedure Code was also attached.

In Management Companies, one does not always work on ships that are fully managed by the concern. An Owner may be managing his own ship, but would have taken all crew from the Management Company.

So you find yourself working for a particular Owner, who has his own SMS Manuals, wherein they have enumerated and elaborated all procedures and check lists in their own way. You find yourself plodding through 700 to 1000 pages of instructions at the start of your tenure, in order to be familiar with it, implement it and be audited (Safety Audits) successfully.

The next ship may belong to a different owner and the process is repeated, where you have to start from scratch.

One can see how conceptual approaches differ from company to company by the imagery below.

Courtesy iStock

Okay. The ISM Code has now been activated by the installation of the Safety Management System on all ships, however divergent they may be from company to company.

As far as the Ship Owner or Ship Manager is concerned, the two main entities involved in the implementation of the ISM Code are A. The Office and B. The Ship.

The Office had to first set up their system before asking the ship to implement Safety Management Systems.

A Safety and Quality group needed to be formed, who would be responsible for

Setting up procedures in line with the relevant ISO standards in the Office and ensure all personnel in the Office become familiar with it.

Enumerate guidelines, procedures in the form of Safety Management System Manuals for their ships to follow.

In actuality, it proved to be a mountainous task.

Some companies, Managers, went in search of experts in the field, within the Maritime industry and without, and hired them to formulate and produce the necessary procedures.

Some companies - I am aware of at least two Japanese companies who did this - took several of their seasoned Captains and Chief Engineers, put them into one room, gave them all the facilities they required, and told them to produce Safety Management System Manuals in accordance with the provisions of the ISO standards.

Most companies produced exhaustive Manuals, running into several volumes. I do not think any one person would have read through them from cover to cover.

Most companies edited their previous circulars and introduced them, if they were found pertinent to any Article of the ISM Code.

The ISM Code became mandatory for Oil Tankers and Bulk Carriers in 1998 and for other ships in 2001.

As far as the Master and Chief Engineer were concerned, this became a double edged sword. They were never sure that the numerous ‘check lists’ that came to be in vogue as part of the Company’s Safety Procedures were being complied with clause by clause, or were the items being ticked off without a formal check by the ship’s staff.

An example is the Unmanned Machinery Spaces (UMS) check list that is supposed to be used at least twice a day. This is one of the ship specific ‘check lists’ that is supposed to be generated by the ship and, after approval from the Office, put into use on board.

I have found that, on many ships, the Chief Engineer who first drew up and implemented the check list, had gone berserk and had made it so detailed that the Engineer who is supposed to check, finds himself spending more than an hour of his time in checking and noting down every parameter of every bit of machinery - and doing it twice a day.

In this period, the shipping industry had made large technological strides. The change from analog to digital had had a very substantive impact inside the Engine Room.

What had been a round the clock watchkeeping in the Engine Room, with a total of 10 alarms on a display panel in the 1970s, had turned into an “Unmanned Machinery Space” that could be left to itself for a major portion of the voyage, with only minimal personnel interfacing, because of more than a 1000 points being automatically monitored, various operational tanks getting filled automatically, with readout displays at the touch of a button and a complete printout of all parameters every noon - more often, if the timers are set.

On top of this kind of parameters’ information overload, to expect an engineer to fill in by hand - in minute squares on the paper of the check list - every parameter of level, pressure, temperature and other details was, in many ways, foolish.

After a while, it became counter productive, as they started just copying previous data, without checking present conditions.

The time spent on correctly filling up this check list , twice a day, was about 4 man hours, maybe a little less.

In the last decade of my seagoing career, I was able to make several far reaching changes to how the Engine Room staff approached a morning check and a night check. Emphasis was on physically checking the operating parameters that were not being monitored by the hundreds of sensors installed. A thorough round twice a day, although an essential part of operation, was made simpler by not noting every minor detail in a ‘checklist’. Instead, posted on each bit of machinery was a placard that gave the details of what are normal and what are abnormal parameters and what to do when abnormalities are found. It speeded up the time spent on checks.

Diverging from the above thought process, how would one teach a junior to listen to the sounds and noise made by each bit of machinery?

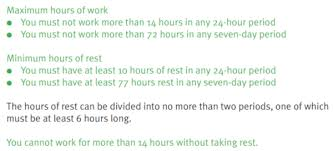

Mandatory Rest Hours = Minimum Manning

With STCW standards introduced, along came something that had never been heard of on ships - mandatory “Rest Hours”. It became mandatory for each individual to keep a record of his or her rest hour periods over every 24 hour period. It had become mandatory to give everyone so many hours of rest in one 24 hour period, with a weekly cap of a certain number of hours. A land based mandatory practice was thrust upon the shipping industry, without any forethought to consequences.

Before these mandatory “Rest Hours” came into existence, we were doing quite well. 2 or 3 days of 14 to 16 hour work periods used to be followed up by at least a day off, with lessening intensity of work for a couple of days, gathering momentum once again over the next week.

It was a peaceful coexistence between intense work and sufficient rest, with no adherence to 54 hours work in a week or 8 hour work in a day.

The work got done, maintenance levels were kept high, the ship did not suffer.

Courtesy Arkmarine Solutions

A Seafarer’s Compilation of “Rest Hours” on a Daily Basis on the Ship’s Computer

Moreover, with UMS came an 8-to-5 working hour culture.

And, to top it all off, the Owners and Managers managed to convince the Classification Societies to reduce manning on ships by issuing “Minimum Manning Certificates” with less personnel on board.

What was 50+ (manpower) in the 1970s, became 30+ in the 1980s, 20+ in the 1990s and 15 in the 2000s.

With reduced manning and increased rest hours, how does a Chief Engineer get maintenance work done - for example, a complete generator overhaul - when 2 of the already reduced staff keep going off to fill check lists of pressures, temperatures and the like?

In the 1970s and early 1980s, I would have at least 8 people working on the generator overhaul - 12 hour workdays - and complete the work in about 4 days.

In the 1990s I could put only 2 or 3 people to work on the generator overhaul because I had only that many hands. Along with this and the compulsion of “Rest Hours”, this generator overhaul started extending to 7 or 8 days, mostly getting completed just hours before reaching port, where all three generators are required for arrival. (Extra load due to bow thrusters, more deck machinery starting etc).

Due to this, many Chief Engineers started avoiding generator overhauls, even if overdue. Result? Breakdowns.

Even Main Engine work suffered. After a long pilotage during which the Engine Room is manned, the watchkeepers have to be given rest, by law. Because of this, no work would be done. This was compounded by short stays in port, Car Carriers being classic examples, with 3 or 4 hours stays in port.

With less maintenance work being done, the skills that go with the job and the intimate knowledge of machinery died many deaths.

Another aspect of reduced manning was that only two or maximum three people would be in attendance in the Engine Room during manoeuvering which, essentially, can be classified as a “Critical Operation”. In the event of any emergency in the Engine Room or on deck or in the Steering Gear Room, sometimes one has to leave the Engine Control Room unmanned, to attend to that emergency.

Not a safe practice as far as the ISM Code or the ship is concerned.

In many of the Engineering disciplines, the term “Factor of Safety” is used. Factor of safety (FoS) is the ability of a system's structural capacity to be viable beyond its expected or actual loads.

Another definition in ‘Solid Mechanics’ : The definition of the safety factor is simple. It is defined as the ratio between the strength of the material and the maximum stress in the part. What it tells us basically is that in a specific area of the model, the stress is higher than the strength the material can bear.

In each discipline, it has a numerical value, arrived at through different formulae, but all indicating how safe that material or structure is.

The higher the number derived, the lesser the chances of a failure.

Applying the same - in principle - to human resources, with the reduction in trained manpower, that too experienced lower category crew, we were deliberately putting ourselves at risk, as we had drastically reduced the ‘human ‘Factor of Safety’.

With bare minimum manning - I have sailed on one ship with just 13 on board - we were systematically reducing the Factor of Safety drastically. Accidents then happen.

The Company’s findings? “Human Error”.

When an accident occurs, time lost and dollars lost in bringing the ship back to 'Fit for Sea' condition will definitely outweigh - by a thousand times - the salary cost of having two junior engineers on the roster, who would have made a difference.

The present trend in most companies of not having cadets or junior engineers to save on expenditure, is most worrisome. With the present attrition rate of between 8 to 10 years for a seagoing career, where will fresh candidates come from? Where will the experience come from to handle emergencies?

Overall impact - less and less work is done. The staff have lesser and lesser experience, so it takes longer and longer to carry out a particular job. And there is no guarantee that the job is done - parts assembled - correctly.

These days, are Main Engine Main Bearings, Cross Head Bearings, Bottom End Bearings being opened by ship’s staff for survey? Most likely, no. A mistake made can prove to be very costly for the company.

These days, are Main Engine Turbochargers overhauled by ship’s staff? Most likely, no - for the same reason.

Check lists filling was now holding greater prominence than the actual physical parameter check - all for filing purposes, to show an Auditor. We were starting to lose touch with reality.

Instead of a System working for you, you now find yourself working for the System.

If a contingency or a condition were to exist on board that had hitherto not taken place, the reaction of the Owners and Managers, on their parts, was to bring another ‘check list’ into the already overburdened system. It was more or less akin to telling the authorities that ‘we have done our best - we have given them a ‘check list’ - not our fault if they did not follow it”.

Whereas, in actual fact, behind all this, that emergency, that contingency, that condition may have arisen due to some odd spares not supplied or a request for workshop assistance for carrying out a particularly difficult job had not been taken seriously in the Office or a dysfunctional detail noted and informed that had not been responded to.

For example, before the days of ISM, I sailed on a ship where the Engine Room Log Book had Departure Port entries “Main Engine tried out at ==. Steering tried out at ==. CPP (Pitch Propeller) tried out at ==.”

What it did not mention was there was no back up for the hydraulics of the Pitch Propeller. The Standby Hydraulic Pump had failed 8 months beforehand and a Spares Requisition for the same had been pending for that long. To make matters worse, the emergency system to bring the pitch to ‘full ahead’ was not working and nobody had queried it, neither the Office, nor the ship’s staff.

(In this particular instance, I had stood my ground and insisted that the vessel would not sail without the Standby Pump being fully operational. After cargo, we went out to anchorage and waited == all of 8 hours. The spares were flown in).

If the same scenario were to exist today - after the implementation of the Company’s Safety Management System and its many ‘check lists’, if the vessel is unable to move and is stuck in mid sea because of the failure of the running (second) hydraulic pump, the ‘check list’ will show the following entry.

“Has the CPP been checked and tried out?” —- “Yes”.

Who will accept responsibility for the failure and be found accountable?

I leave it to your judgement.

INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL AUDITS

In the initial stages of the implementation of the ISM Code, there was confusion and obvious transgressions. An example was that of a Senior Superintendent carrying out an Internal Audit of a ship that came under his own umbrella.

But soon, most companies realised that the only recourse was to have a separate team for implementing all aspects of Safety and Quality Assurance. Some went to the extent of ensuring that this Safety and Quality team reported directly to the top Management, bypassing middle management, empowering them to issue ‘show cause’ notices to erring Superintendents. There was a lot of angst within the office at these sweeping powers being given to a newly formed group, but it withstood the test of time.

The 2000 to 2005 period saw this internal tussle slowly fading away, with the Safety and Quality group gaining the upper hand.

2005 and beyond saw the Audits - Internal as well as External - actually having an impact, as Non Conformities were set time limits and had to be rectified within that period. The ship’s Superintendent was taken to task if this rectification did not take place. Some amount of ‘accountability’ emerged.

The Internal Audit, carried out by the Company’s Safety and Quality wing, actually became a tool wherein the ship could manipulate the Auditor and force the Operations Department to carry out and execute jobs that had been postponed or kept pending, citing costs.

Some companies - the smaller ones who did not have their individual Safety and Quality department - relied on third party auditors for their Internal Audits. It was more to prove to the External Auditor and show the documentation that they have been doing their part in auditing their ships than in the improvement of the ship.

I have had a few confrontations with these free lance Internal Auditors. For the purpose of showing themselves as good auditors to the company that had given them the contract, they come to the ship with an avowed agenda to find defects on the ship, even when there aren’t many.

A good auditor will, when he finds a well run ship, only pass a few comments on items that can be improved upon.

Whereas the freelance auditor will try to write up at the least about 70 or 80 odd non-conformities, even on well run ships, probably to prove his efficiency and knowledge.

On three such occasions where the auditors went on a spree in handing out non-conformities, I crossed swords with them during the post audit meeting, cancelling irrelevant non conformities and also cancelling others which showed that the auditor was ignorant of either the technical expertise required or standard ship board practices. Net result? The Captain and I refused to sign any of the documents associated with the Internal Audit. There was no backlash.

Both the audits, Internal and External, are the necessary evils that we have to comply with. May as well come to terms with it and prepare well for them.

My philosophy as far as Internal and External Audits were concerned was to conduct an audit of my own within two weeks of my joining a ship, correct the flaws, instruct the staff and periodically check on them. So there was no panic or intense work needed prior to the audit date.

And, finally, finding the lamb for the slaughter

The Fiction

The Fact

The Master is the centre of the target. Other ship's staff are in the gradually increasing circles.

Courtesy Dreamstime.com

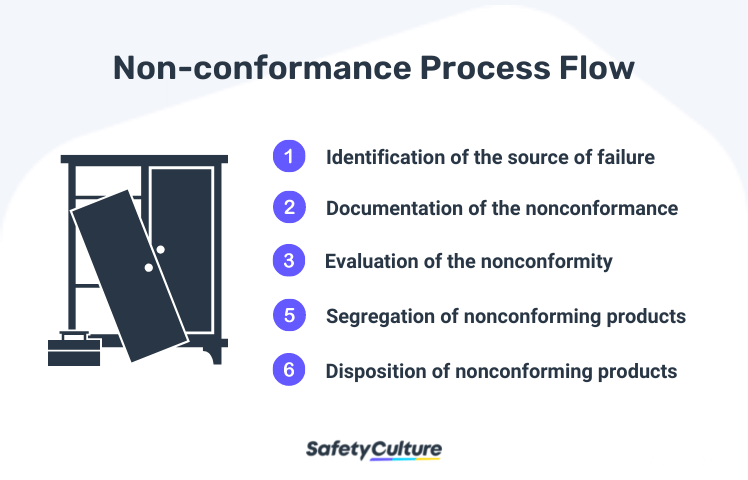

Non conformities, corrective actions, root causes is a vast subject.

A narrative for another time, perhaps?

===== Blog 112 continues on a different subject =====

Comments