Blog 107 == A Glimpse of Life on a Car Carrier and the Cargoes Carried = I Bid Goodbye to Sea Life

- ranganathanblog

- Jan 11, 2023

- 9 min read

"Marine Musings 35"

Operations

Life on a Car Carrier was always extremely busy. It goes from 0 to 200 in 60 seconds of your joining, especially if there is no parallel sailing with your predecessor. You may have just 2 to 3 hours to take over before the vessel sails out of that port.

On all the Car Carriers that I sailed on, this was the case - with the last ship’s handing over being done at the gangway, the handing over being restricted to a hand shake.

Car Carriers are fast compared to bulk carriers, doing between 18 to 21 knots. So, time at sea on voyages that are considered lengthy, actually become short.

Ports come in a cluster, with several ports being scheduled one after the other. A typical schedule - for instance in Europe - would be

2 days, 1 day before arrival -

Get ready and start change over to Low Sulphur Fuel Oil, logging every detail.

Fix mesh to funnel outlets to prevent the smallest bit of soot from escaping into the atmosphere.

(If US ports, conform to CFR (Code of Federal Regulations) 164.25 and carry out all checks, document the results.)

Ensure all personnel get sufficient rest.

Assume date is 01st of a particular month -

Arrival first port 0800H after an 8 hour pilotage upriver. All fast and ramp down, discharge starts. Discharge completed at 1100H. Pilot already on board. Ramp up, engine tried out only after ramp is secured. Already ‘singled up’, let go and out we go. For such a structure with such a massive sail area, only one tug has been ordered - Charterer’s instructions. Use Bow Thruster at full pitch. (If this happens for a long enough period, the thruster trips on ‘high coil temperature’ and needs at least an hour to cool down before it can be restarted.) So, the Chief Engineer calls Bridge to advise Bridge to reduce pitch. Pilot is unhappy.

Vessel now in channel. Harbour Pilot gets off and River Pilot takes over.

6 hours or less downriver, he gets off.

Vessel is at sea, increases to full speed.

4 hours later at 2100H, Bridge starts reducing engine speed, tries out engine, picks up Pilot at 2200H.

Upriver pilotage for 4 hours, alongside at 0200H / 02nd.

Ramp down, cargo starts, completed by 0600H in the morning.

Downriver to the next port.

Repeat for the next 8 to 10 days.

This schedule plays havoc with the rest hours for all staff, with them becoming more haggard day to day.

Another facet of a car carrier are the restrictions imposed on main engine work due to the lack of height.

The entrance deck to the ship is directly above the Engine Room. On a conventional ship, this would have been the open space right above the main engine, after which would be the boiler spaces leading to the funnel.

With the height reduced above the Main Engine, the piston of an in-line engine has to be removed and refitted in 2 stages, increasing the number of hours required to decarbonise a ‘unit’.

The ‘Anna’ was the exception as it had a Kawasaki V- type 16 cylinder engine, which required low head room only, ideally suited for car carriers, but not commonly used due to many factors. Complexity in design, need of staff more experienced in V-type, being a medium speed four stroke engine it requires gearing to step down the rpm of the propeller, the total quantity of spares carried increases and other factors.

With low head room and in-line engines, the piston cannot be extracted in one single operation, due to the length (or height) of the piston and piston rod. It has to be partially lifted, rested on a platform that is inserted, the clamping arrangement changed to below the piston and then lifted out, reversing the process when fitting back.

Or, two of the cylinder cover studs are removed every time, to give sufficient space for the piston rod to be eased past the studs. Even 1 degree of list can make removal difficult.

On a few Car Carriers, the decks above are designed to give just sufficient head room - a matter of a few centimetres - to lift out the piston in one go.

Cargo Operations

The Car or Vehicle Carriers are, by far, the most interesting type of all types of ships.

The cargo they carried in the past versus the cargo they carry these days has changed dramatically.

In the 1980s, cars and trucks were the only cargo.

Cars would be arranged in military precision, in the car decks. All they lack is the ability to salute.

The entire scenario of loading cars, especially in Japan, is one worthy of being called a ‘military drill’ because of the precision. It is akin to watching one or several robots programmed to carry out multiple, repetitive tasks.

A batch of 10 drivers drive the 10 cars up the ramp of the ship, followed by a van. At the ramp, they stop for a few seconds where the tally clerk checks that particular car in to his tally sheet and the driver is told to drive to, say, # 3 Deck Forward Port side.

When the drivers of these ten cars reach the area, they leave the cars in or around the area, get into the van that had followed them and get driven back to the yard where thousands of cars are parked, only to get into the next ten cars and repeat the process.

At the spot where these 10 cars are left, three or four drivers get in and quickly reverse each car into its final position and park each one very close to the adjacent one, literally maintaining a gap of a maximum of 3 inches between cars.

The driver reverses and parks the car in its spot and, in seconds, carries out a routine of switching off the ignition, pulling the hand brake and exiting the car just as the next car is being reversed into exactly the space where he had been standing a few seconds ago.

The moment the first car is in position, another team of 4 surround the four points of the car with nylon straps, with hooks at their ends. One hook goes on to one spot on the underside of the car, the other hook goes on to either a hole in the deck or a clamp. A quick pull on the strap - something akin to tightening your seat belt in a car - and the strap tightens to keep the car immobile. 4 corners, 4 straps. Again and again, the same routine follows.

Depending on the number of drivers being available, this same scenario is being played out at 10 or more places at the same time, all cargo being distributed evenly to maintain the ship upright and to not destabilise her.

All the while, to prevent accumulation of the exhaust from cars, massive blowers - 20 to 40 in number, depending on the size of the carrier - are forcing the air into all the car decks. The noise is tremendous, one has to compulsorily wear ear protectors. One can feel the heavy pressure of the air exiting the ship at the stern ramp entrance. If the atmosphere is cold, this blast of air can freeze you if you have not protected yourself with warm clothing.

Simultaneously, segregation of the same type of cargo for different ports is taking place. Each car weighs, say, 2 tons. So, if one discharge port is scheduled to receive 800 cars of the same model, all 800 will not be stowed in one cluster, next to each other, for reasons of ship stability and list. These 1600 tons will be distributed to various decks, various places.

In the pre-computer and internet days, a thick sheaf of tens of copies used to be held by stevedores, foremen, tally clerks, Chief Mates, Duty Officers to ensure that the correct cargo goes to the designated port.

Now, all carry an i-pad or a tablet and, through the internet, access all data. Bar codes made identification simpler. QR Codes and bar codes are now scanned at the point of entry to the ship or departure from the ship that identifies the car, the model, the chassis number, where loaded, where stowed, where destined and triggers an alarm if being wrongly discharged.

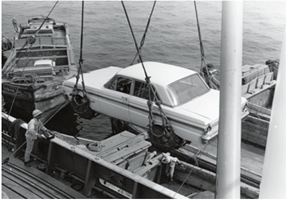

In the initial years, cars were loaded into holds by mounting them on saddles and lifted by cranes.

In the late 1960s came a concept of RO/Ro Lo/Lo, where cars were loaded and bulk cargo was also loaded, soon abandoned to pave the way for more specialised ships.

Then came the Pure Car Carriers (PCCs) with stern ramps and fixed decks, so that cars can be driven in. The stern ramp model was copied off the ferries. The height between each deck allowed only cars and SUVs to be loaded.

The pure car carrier very soon expanded into a Pure-Car-and-Truck Carrier (PCTCs). To fit a high roofed truck, almost every alternate deck on the ship was made liftable, to increase head space. With the liftable deck panels at the low level, cars were loaded. With the panels being lifted and more head space available, trucks were loaded.

Courtesy MacGregor.com

From looking at the fixed deck on the left of image, it can be seen that the liftable deck panel has been lifted by nearly 2 metres.

I have had the opportunity of maintaining and operating both the above equipment. To locate the truck or the vehicle containing the hydraulic lifter at the exact points as marked proved to be a measure of skill. Then the side jacks are deployed to take the weight off the tyres. Next the X-shaped lifter is deployed. Once the deck is lifted right up, four resting pivots fall into place at the four corners, then the deck panel is lowered by a few inches to rest on these pivots. Depending on the deck panel to be lifted, there are cut outs provided on the hydraulic lifters to not exceed the height to which the deck panels need to be lifted. Even then, care has to be taken that the liftable deck panel does not get squeezed into whatever is above.

Normally, the loading plan is received on board a few days before arrival and nearly two days are used up in lifting up deck panels to set them according to the cargo plan.

This type of cargo that used to be lifted up by cranes and loaded into ship’s holds, are now being put onto trailers, driven in and the trailer secured with lashings.

Note the heavy chain lashings used for the heavier cargoes.

Nylon straps are used for car lashings.

The above 10 photographs show the size and orientation of the different types of cargo we used to carry, all of them loaded on board within minutes.

I reflect on the complexities of carrying this same cargo on General Cargo Ships of yesteryear.

The Pegasus Leader and Alioth Leader, besides having liftable deck panels, also had something unique - a 200 ton Elevator Deck on # 7 Deck, about 25 metres into the ship on the starboard side of midship. It was, essentially, a large rectangular platform with hydraulic cylinders under them to lift them. (Am not certain what capacity, could be more than 200 tons, not less, but very heavy cargo was loaded).

A 200 ton load can be driven up the stern ramp, centred on this Elevator Deck and this whole deck can be lifted up by nearly 10 metres, to come level with # 9 Deck, driven off the Elevator and the trailer parked, stowed, lashed on # 9 Deck, strengthened for this purpose. Huge hydraulic cylinders lifts up the Elevator Panel or deck very slowly. We carried this type of heavy consignment - nearly to the capacity of this Elevator Panel - practically every voyage.

From the time this heavy cargo comes into the ship till it is lashed - time taken would not have exceeded 12 minutes. With a conventional cargo ship with heavy lift Stulkens, it would have taken at least 2 hours.

I am not certain, but I do not recall any of the Car Carriers that I sailed on ever being loaded down to her marks, in spite of the heavy cargo carried. Stability and the necessary GM were maintained by use of ballast, if need be.

From Pure Car and Truck Carriers, these juggernauts have become Super Carriers, the only limitation being the height at the mouth of the ship. Cargoes of any shape, size, weight - they are all loaded so long as they can be driven in.

On the Pure Car Carriers we carried an assortment of the more pedestrian Japanese, Korean and Chinese cars to the USA and Europe, with a few high end sports cars of those brands.

From the US, we carried US made cars (very few) to Europe and Asia.

From Europe, we carried really exotic, high end, cars - Mercedes, BMWs, Porches, Aston Martins, the occasional Rolls Royce, a few Lamborghinis and Maseratis - from Europe to Asian ports. The exotic cars were for Dubai and Singapore, all Rolls for Hong Kong. These costly cars would be parked and lashed with a lot of space around them, as befitted their costs, not packed like sardines.

(Being a vegetarian, I have not seen sardines packed, hence cannot vouch for its authenticity).

My last Ship at sea - the "Polaris Ace"

My last ship was the “Polaris Ace”. I had already (nearly) decided to quit sailing after completing my tenure on the “Polaris Ace”. I was asked to join this ship on an emergency basis at Durban due to the last Chief Engineer having a family emergency. (Normally, crew changes do not take place in Durban, South Africa.)

My plan was to sail till the year end (2008) and call it quits.

Just 2 days before I was to fly out to Durban, out of the blue, I received a job offer as a Vessel Manager / Consultant for the US entity of Maersk Line, where I was called to begin service immediately. Mr. Ganapathy, whom I had known very well during our days together in Barber's, who was then working for Maersk USA, called and offered me the job.

I did not want to decline this promising an offer of a job ashore and asked BSM Bombay if they could send someone else. At such a short notice, they had none to send. I explained the situation to Maersk and they asked me to start after a month.

Barber’s agreed to relieve me within a month.

True to their promise, they relieved me in Argentina.

No fan fare. I left as quietly as I had joined 38 years ago.

Thus ended 38 years of a sea faring life, 6 with Sisco’s and 32 with Barber Ship Management.

===== "Marine Musings 36" and Blog 108 Continue =====

I am disappointed at barber managent. They should have done something to acknowledge and appreciate your services for 32 years. A get together either in or Hongkong ar bsm office, a speech anda certificate as a minimum and awriteup in bsm newsletter.

Guru